Data, disciplines, and the pressures reshaping four-year competition

Community college bachelor’s degrees are often discussed as if they are still emerging or hypothetical. The data suggests otherwise. These programs already exist at meaningful scale, they are concentrated in specific fields, and they are expanding in ways that intersect directly with enrollment pressure at small, tuition-dependent four-year institutions.

Recent policy debates, such as the one unfolding in Iowa, have drawn renewed attention to this trend. But Iowa is better understood as an early signal than an exception. The larger story is already visible in national inventories and enrollment data.

This post draws primarily on the Community College Baccalaureate Association’s national program inventory, supplemented by recent reporting and practitioner perspectives, to clarify what community college bachelor’s degrees actually are, where they are offered, and why they matter.

How widespread are community college bachelor’s degrees?

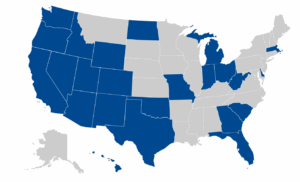

As of the most recent CCBA inventory, more than 200 community colleges are authorized to offer bachelor’s degrees across 24 states, with 700+ distinct programs already approved or operating.

This is not a marginal footprint. In several states, community college bachelor’s degrees have moved from pilot status to a normalized component of the postsecondary landscape. In others, legislative proposals suggest that additional expansion is likely.

Importantly, authorization tends to be paired with explicit workforce rationales. States cite transfer leakage, place-bound learners, and unmet regional labor demand as justifications for allowing community colleges to move into the bachelor’s space.

Figure 1. Map of states authorizing community college bachelor’s degrees. Data source: CCBA inventory

Where are these degrees concentrated?

When you look closely at the CCBA inventory, one thing becomes clear pretty quickly. These bachelor’s degrees are not scattered across the curriculum. They show up again and again in the same kinds of fields, and that repetition matters.

Health-related programs lead the way. Bachelor’s degrees tied to health sciences, healthcare administration, health information, and related areas appear across many states. In most cases, these programs build directly on associate-level clinical or technical preparation. They exist because a bachelor’s credential is increasingly required for advancement, licensure, or leadership roles, not because students suddenly want a different kind of academic experience.

Information technology is another major concentration. Programs in IT, cybersecurity, networking, information systems, and application development are common. These degrees are often designed for students who are already working in the field and need a bachelor’s degree to move forward. The credential is the bottleneck, not the skill set.

Business and management programs also show up frequently, particularly degrees focused on management, organizational leadership, supply chain, logistics, and applied business. These are not traditional residential business programs built around internships and campus recruiting pipelines. They are structured for working adults who want upward mobility without stepping away from employment.

Advanced technical fields form another clear cluster. Manufacturing engineering technology, industrial automation, instrumentation, digital manufacturing, geomatics, and similar programs reflect strong alignment with regional industry needs. In many cases, community colleges already had deep technical expertise at the associate level. The bachelor’s degree simply extends that pathway rather than reinventing it.

Human services and public safety programs round out much of the remaining activity. Degrees in human services, emergency management, homeland security, and public safety appear consistently, especially in states with large rural or place-bound populations. These programs often support public sector and community-based careers where credential thresholds matter for promotion and pay.

Taken together, the pattern is hard to ignore. Community college bachelor’s degrees concentrate in applied, workforce-facing fields where students are pragmatic, employers are credential-sensitive, and the return on investment question is front and center.

Table (Coming Soon)

Community college bachelor’s programs by discipline cluster

Columns: Discipline category | Approximate share of programs | Representative degree titles

What kinds of bachelor’s degrees are being awarded?

The most common credential awarded is the Bachelor of Applied Science (BAS). This is by far the dominant degree type in the CCBA inventory.

Other degree types appear far less frequently:

Bachelor of Science (BS)

Bachelor of Arts (BA)

Bachelor of Applied Technology (BAT)

Bachelor of Technology (BT)

Bachelor of Business Administration (BBA)

Bachelor of Arts in Applied Science (BAAS)

The prevalence of applied degrees is not accidental. These credentials are designed to accept applied associate degrees with minimal credit loss, serve working adults, and prioritize applied competencies over traditional liberal arts sequencing.

Suggested Figure 2

Distribution of degree types awarded by community colleges

Data source: CCBA inventory

Why cost changes the competitive equation

At the center of this conversation is cost. Community colleges operate at a very different price point than most four-year institutions, often supported by public funding structures that private colleges and, in some cases, regional public universities do not have access to. When bachelor’s degrees begin to appear at that price point, the competitive landscape shifts quickly.

There will always be students who want a traditional residential experience and a degree from a four-year institution. That preference still matters, especially for some first jobs. But cost has a way of reshaping decision-making over time. For many students and families, the question becomes less about where a degree comes from and more about what it enables them to do, how much debt it carries, and how close to home it can be completed.

This is why policy debates like the one unfolding in Iowa resonate beyond a single state. They surface a broader tension around affordability and access. As lower-cost bachelor’s pathways become more common, institutions that rely heavily on tuition revenue feel that pressure sooner and more intensely.

Infrastructure, appearance, and uneven pressure

Another dynamic worth naming is how unevenly this pressure is distributed. Many private four-year institutions carry high fixed costs tied to residential infrastructure, student life, and campus amenities. Those features are often central to their value proposition, but they are also expensive to maintain and difficult to scale back.

Community colleges face their own constraints and long-standing stigma, particularly around perceptions of quality or prestige. But they are typically not burdened by the same residential cost structures. That difference matters. When enrollment softens, institutions whose primary value proposition is also their largest cost center have far less room to maneuver.

The result is not simply competition between sectors. It is competition between business models operating under very different financial assumptions.

The residential question and the learning lifespan

This shift also raises questions about the role of the residential experience itself. For some students, residential education remains deeply valuable. For others, flexibility, location, and cost take precedence. The system now has to accommodate both realities at the same time.

At the same time, institutions are increasingly being asked to compete across the entire learning lifespan, not just at the point of first entry. Learners move in and out of education. They return for credentials tied to promotion, reskilling, or career change. Pathways built around a single moment of entry struggle to meet that reality.

From this perspective, community college bachelor’s degrees are less about replacing four-year institutions and more about reshaping when and how bachelor’s credentials are accessed.

Language, labels, and growing confusion

One final complication is worth noting. Community colleges are offering four-year applied bachelor’s degrees at the same time that some four-year institutions are introducing three-year, 90-credit bachelor’s programs, often using similar “applied” language.

These programs are not the same, but the labels are increasingly hard to distinguish. Over time, that confusion is likely to affect advising, marketing, and policy conversations, even as it accelerates competition for students who are already navigating a complex system.

Why this matters now

Community college bachelor’s degrees sit at the intersection of several slow-moving but consequential shifts. Enrollment continues to grow at community colleges. Certificates and short-term credentials keep expanding. Public four-year institutions are seeing modest gains, while many private four-year colleges continue to experience declines.

Layered on top of that is a quieter development that deserves attention: the gradual emergence of three-year, 90-credit bachelor’s degrees at four-year institutions. These programs are still limited in number and scope, but they point in a similar direction. Many are described using “applied” language, or framed around efficiency, acceleration, and reduced cost. Even where the models differ, the signal is consistent. Institutions across sectors are searching for ways to shorten time to degree and lower the price of a bachelor’s credential.

What makes this moment different is that these shifts are happening simultaneously, but unevenly. Community colleges are expanding four-year applied degrees at scale. Some four-year institutions are cautiously experimenting with compressed bachelor’s pathways. At the same time, students are becoming more sensitive to cost, location, and return, particularly as delayed entry and re-entry become more common.

The result is not a clean transition from one model to another. It is a period of overlap, experimentation, and growing confusion around labels like “applied,” “accelerated,” and “workforce-aligned.” For students and families, those distinctions are often less important than outcomes, affordability, and flexibility.

Taken together, these trends suggest a system slowly reorganizing around access to the bachelor’s degree across time, not just at the point of first entry. Community college bachelor’s degrees are not the whole story, and three-year bachelor’s programs are not a dominant force yet. But both reflect pressure on the same assumption: that a four-year, 120-credit, residential model is the default path for earning a bachelor’s degree.

Institutions that treat these developments as isolated experiments may miss the larger signal. The more important question is whether colleges are prepared for a landscape where multiple bachelor’s pathways coexist, compete, and blur together, and where learners expect options that fit their lives rather than the other way around.