Beyond the Tenure Track: How Generative Mentoring of Adjunct Faculty and Department Chairs Enhances Institutional Quality and Student Success

gregpillar

on

March 1, 2025

In higher education, mentorship is often regarded as a fundamental component of faculty development. However, traditional mentorship models tend to prioritize tenure-track faculty while neglecting adjunct instructors and department chairs. These two groups play crucial roles in institutional success but often lack the structural support necessary for professional growth.

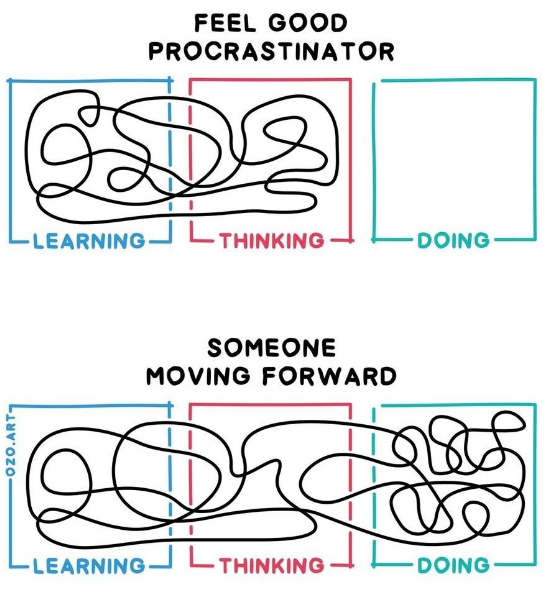

Furthermore, traditional mentor-mentee models are often inconsistent and may not include structured check-ins or points of reflection on how well the relationship is progressing. Many of these mentoring arrangements, while well-intentioned, tend to fizzle out over time without a sustained framework to ensure longevity and effectiveness. This is not to say that successful mentorships do not exist—many flourish—but the inconsistency in traditional models presents a challenge that institutions must address.

Drawing on concepts from Hope Circuits (Riddell, 2024), this article explores how mentorship can be reframed as generativity, focusing on sustaining faculty development through systemic mentorship structures. By incorporating mentorship constellations (Vandermaas-Peeler & Moore, 2023) and reverse mentoring (O’Connor et al., 2025), institutions can create faculty support systems that enhance professional resilience, institutional belonging, and student success. These models provide a structured framework that ensures persistent and consistent mentoring relationships, preventing mentorships from fading over time due to lack of structure or engagement.

The Institutional Gaps in Faculty Mentorship

The Problem with Faculty Development Models

Faculty development programs often cater primarily to tenure-track faculty, with adjunct instructors and department chairs receiving little to no structured support (Pillar, 2025; Faculty Focus, 2024; Pearson & Kirby, 2018). Without dedicated mentorship, these groups struggle to navigate institutional expectations, contributing to burnout and disengagement (Cain et al., 2024; Zarrow, 2013).

At smaller institutions, department chairs juggle administrative, instructional, and leadership responsibilities, yet many receive no formal training in mentorship or institutional leadership (Pillar, 2025). Similarly, adjunct faculty, despite comprising nearly 50% of the academic workforce (AFT, 2022), often find themselves excluded from professional development initiatives (Gibson & O’Keefe, 2019). Addressing these disparities is critical for fostering institutional effectiveness and faculty retention.

Moreover, many traditional mentorship programs lack formal structures for ongoing evaluation and reflection, leading to relationships that gradually diminish in effectiveness. Without regular touchpoints, mentor-mentee relationships can drift apart, leaving mentees without continued guidance and mentors disengaged. Reverse mentoring and mentoring constellations provide structured avenues to embed accountability and sustained engagement into mentorship programs. By fostering mentorship as a continuous cycle of learning and growth, these models help maintain active and meaningful relationships rather than allowing them to fade over time.

The Overlooked Needs of Adjunct Faculty

Adjunct instructors play a significant role in student learning but often lack job security, access to resources, and inclusion in governance structures (Pillar, 2025). Studies show that institutions that integrate adjuncts into structured mentorship networks report improved faculty engagement, instructional effectiveness, and student outcomes (Pillar, 2025).

One approach to addressing these issues is mentorship constellations, in which adjuncts have access to multiple mentors who provide guidance in teaching, career advancement, and institutional navigation (Vandermaas-Peeler & Moore, 2023). Such models foster a sense of belonging and professional identity, countering the isolation many adjuncts experience. Additionally, research highlights the need for institutions to systematically integrate adjunct faculty into institutional governance and leadership pathways (Pillar, 2025). Ensuring that adjuncts have access to career progression through mentorship programs enhances their engagement and retention (Defining Mentoring, Elon University, 2024).

For adjuncts teaching online—particularly those who are fully remote and physically distant from their institution—mentorship becomes even more critical. Studies indicate that online adjunct faculty often feel isolated and disconnected from institutional culture, which impacts their effectiveness and retention (Pearson & Kirby, 2018; Puzziferro-Schnitzer & Kissinger, 2005). Strong mentoring programs tailored for online adjuncts, such as virtual mentoring models and structured peer networks, provide a way to mitigate this isolation while enhancing teaching quality (Puzziferro-Schnitzer & Kissinger, 2005). Programs that include ongoing, interactive professional development and structured mentorship relationships have demonstrated success in retaining online adjuncts and improving student outcomes (Pearson & Kirby, 2018a).

Riddell’s Hope Circuits (2024) provides a framework for enhancing adjunct mentoring by emphasizing systemic support structures that foster continuous engagement, professional identity formation, and institutional belonging. By integrating trauma-informed mentoring practices and emphasizing long-term faculty resilience, institutions can create sustainable, meaningful mentorship experiences for adjunct faculty regardless of their instructional modality.

The Hidden Labor of Department Chairs

Department chairs often serve as institutional linchpins, balancing faculty needs, administrative directives, and student concerns. Yet, their role is frequently under-supported, and, due to lack of guidance, mentoring, and/or training, a significant period of time may pass where chairs find themselves working harder, not smarter. Many chairs do not immediately recognize the operational efficiencies and collaboration opportunities available to them, which could streamline their workload and enhance their effectiveness (Pillar, 2025). Without clear mentorship structures, new chairs may struggle with unnecessary burdens, leading to stress and inefficiency.

Institutions must rethink how they support department chairs as both mentees and mentors. Reverse mentoring—where chairs learn from adjuncts and early-career faculty—can foster a collaborative culture and ensure chairs remain attuned to faculty and student needs (O’Connor et al., 2025; Cain et al., 2024). Reverse mentoring has also been shown to break down traditional hierarchies in academia and foster institutional learning at multiple levels (Seeing Behind the Curtain, Cain et al., 2024). Additionally, mentorship constellations can be particularly effective in providing guidance for chairs, especially in institutions where experienced faculty members have successfully navigated the role before (Vandermaas-Peeler & Moore, 2023). By establishing structured mentoring networks where former chairs provide insights into administrative efficiencies and leadership strategies, institutions can better equip new department heads for success.

Riddell’s Hope Circuits (2024) offers a model for fostering resilient leadership through structured mentorship. By integrating systems of peer learning, guided reflection, and institutional knowledge-sharing, department chairs can transition more smoothly into leadership roles while maintaining their effectiveness as both administrators and mentors to faculty. Institutions that intentionally cultivate mentorship ecosystems for department chairs will ultimately strengthen faculty governance, improve leadership sustainability, and create a culture of collaborative support.

Mentorship as Generativity – A New Approach

What is Generative Mentorship?

Generative mentorship moves beyond the traditional, hierarchical mentor-mentee relationship and shifts toward a reciprocal, growth-oriented model (Riddell, 2024). This approach fosters mentorship as a dynamic, evolving process, rather than a static, one-directional transfer of knowledge. Generativity in mentorship ensures that mentorship relationships remain sustained, meaningful, and adaptable, addressing the ever-changing needs of faculty members at various career stages.

By embedding mentorship in institutional structures, generative mentorship builds long-term resilience and faculty well-being (Riddell, 2024). Instead of relying on sporadic or informal interactions, a generative approach cultivates mentorship ecosystems where faculty members engage in ongoing reflection, knowledge exchange, and professional growth. This model also reinforces the value of mentorship across faculty ranks, ensuring that adjunct faculty, department chairs, and early-career academics receive equitable support in their professional journeys.

Rethinking Mentorship through Constellation and Reverse Models

Mentorship Constellations

Mentorship constellations emphasize that no single mentor can meet all of a faculty member’s professional and personal development needs. Instead of a one-to-one model, mentorship constellations create a network of mentors that faculty can rely on for different areas of growth (Vandermaas-Peeler & Moore, 2023). This approach is particularly beneficial for adjunct faculty, who often lack a clear institutional support system, and for department chairs, who face multifaceted leadership challenges.

By leveraging multiple mentors with diverse expertise, faculty members gain access to specialized knowledge, institutional insights, and cross-disciplinary perspectives (Mentoring Constellations in Global Contexts, 2024). These networks also provide social and emotional support, fostering a sense of belonging that is often lacking in academia. For adjunct faculty, this model helps bridge the disconnect they may feel from full-time faculty and institutional culture (Pearson & Kirby, 2018b).

Studies have shown that institutions implementing mentorship constellations report higher faculty retention rates, improved teaching outcomes, and stronger interdisciplinary collaboration (Research Overview, 2024). Faculty who engage in mentorship networks also experience greater job satisfaction and professional fulfillment, as they are less isolated and better equipped to navigate institutional complexities (Defining Mentoring, Elon University, 2024).

Reverse Mentoring

Reverse mentoring flips the traditional mentorship model by positioning early-career faculty or adjunct instructors as mentors to senior faculty or department chairs. This model facilitates intergenerational learning, ensuring that faculty at all levels stay informed about evolving student needs, technological advancements, and inclusive teaching strategies (O’Connor et al., 2025).

For department chairs, reverse mentoring can be transformational, as it provides fresh insights into faculty experiences, student engagement strategies, and institutional blind spots (Seeing Behind the Curtain, Cain et al., 2024). This model also fosters equitable knowledge exchange, challenging traditional hierarchies in academia and creating space for diverse voices in institutional decision-making.

Institutions that integrate reverse mentoring programs have observed improvements in faculty collaboration, leadership adaptability, and institutional responsiveness to emerging challenges (O’Conner et al., 2025; How Reverse Mentoring Helps Co-Create Institutional Knowledge, 2024). Reverse mentoring also contributes to higher faculty engagement and morale, as it validates the expertise of early-career faculty while encouraging senior faculty to remain adaptive and open to change (Mentoring Constellations in Global Contexts, 2024).

Institutional and Personal Impact

The impact of structured mentorship models extends beyond institutional outcomes to personal and professional faculty growth. At an institutional level, mentorship constellations and reverse mentoring contribute to:

- Higher faculty retention by creating structured, sustained mentorship relationships that foster belonging and engagement (Pillar, 2025; Pearson & Kirby, 2018a).

- Enhanced teaching and learning by facilitating cross-generational knowledge exchange and instructional innovation (Gibson & O’Keefe, 2019).

- Stronger leadership pipelines by equipping department chairs and adjunct faculty with the guidance and skills they need to navigate their roles successfully (Riddell, 2024).

- Increased faculty collaboration by fostering networks of shared expertise and interdisciplinary connections (Pearson & Kirby, 2018a).

On a personal level, mentorship fosters professional confidence, leadership growth, and career satisfaction. Faculty members who participate in mentorship constellations experience:

- Greater career clarity as they receive diverse perspectives and tailored professional guidance (Pearson & Kirby, 2018b).

- Reduced feelings of isolation, particularly for adjunct faculty and online educators who may otherwise feel disconnected from their institutions (Pearson & Kirby, 2018a: Puzziferro-Schnitzer & Kissinger, 2005).

- Higher resilience and adaptability as mentorship relationships offer strategies for navigating career challenges and institutional demands (Riddell, 2024).

- Stronger work-life balance, as faculty who have robust mentorship support report lower stress levels and greater career satisfaction (Mentoring Constellations in Global Contexts, 2024).

By integrating mentorship constellations and reverse mentoring models, institutions can ensure that faculty members not only thrive in their roles but also contribute meaningfully to institutional transformation and student success. The personal and institutional benefits of structured, generative mentorship models make a compelling case for higher education institutions to prioritize mentorship as a central pillar of faculty development.

Practical Strategies for Institutions

For mentorship programs to be effective, institutions must move beyond informal or ad-hoc approaches and develop structured, intentional mentorship frameworks. A well-designed mentorship program should be embedded within faculty development initiatives and aligned with institutional goals for faculty success, retention, and leadership development (Vandermaas-Peeler & Moore, 2023).

A key component of intentional mentorship structures is ensuring broad participation across faculty ranks, including adjuncts, department chairs, and early-career faculty. Institutions that implement structured mentorship initiatives—such as faculty mentoring circles, formal mentor-mentee pairings, and ongoing professional development programs—see higher engagement and faculty satisfaction (Research Overview, 2024). Furthermore, institutions must provide administrative support and resources to sustain these mentorship programs, including incentives, mentorship training, and time allocation for faculty mentors (Pillar, 2025).

Incentivizing Mentorship Participation

Encouraging faculty to participate in mentorship requires institutions to recognize and reward mentorship contributions. Many faculty members, particularly adjuncts and department chairs, already manage heavy workloads, and adding mentorship responsibilities can seem burdensome without appropriate incentives (Gibson & O’Keefe, 2019).

Institutions can promote mentorship participation by offering course releases, stipends, or recognition in promotion and tenure processes (Puzziferro-Schnitzer & Kissinger, 2005). Additionally, mentorship engagement should be formally acknowledged in annual faculty evaluations, awards, and institutional leadership programs (Pearson & Kirby, 2018a). Structured mentorship pathways that offer clear career benefits, such as professional development funding or administrative leadership training, further enhance faculty engagement (Hope Circuits, Riddell, 2024).

Integrating Mentorship into Faculty Onboarding

Mentorship should be embedded into faculty onboarding processes to ensure new faculty—especially adjuncts and department chairs—receive structured guidance from the outset. Institutions that pair new faculty members with mentors early in their careers see higher retention rates and stronger professional engagement (Pearson & Kirby, 2018b). However, effective onboarding should not be a one-time event but rather a continuous developmental process throughout the academic year. New faculty need sustained support to adapt to institutional expectations, instructional challenges, and evolving student needs.

A comprehensive onboarding mentorship program includes orientation sessions, peer mentoring, and structured faculty development plans. While an initial orientation is valuable for introducing faculty to institutional policies and expectations, ongoing mentorship ensures that faculty continue to receive guidance as they encounter real-world challenges in their roles. Regular follow-up meetings, structured check-ins, and opportunities for professional development allow faculty to build confidence, refine their teaching and leadership skills, and integrate fully into the academic community.

Reverse mentoring can also play a key role in onboarding, allowing early-career faculty and adjuncts to share student-centered perspectives and emerging pedagogical innovations with senior faculty and administrators (O’Connor et al., 2025). Additionally, mentoring constellations provide multiple points of support for new faculty, ensuring they have access to a network of experienced colleagues who can offer diverse perspectives and expertise (Vandermaas-Peeler & Moore, 2023). By designing onboarding programs that extend beyond the first semester and into the full academic year, institutions foster an environment where new faculty feel supported, engaged, and prepared to succeed.

Expanding Professional Development for Adjuncts

Adjunct faculty often lack access to institutional resources and professional development opportunities, making targeted mentorship programs essential for their career success and institutional integration (Defining Mentoring, Elon University, 2024). Strong mentorship initiatives help adjuncts develop effective teaching practices, engage in institutional governance, and explore career advancement opportunities (Pearson & Kirby, 2018b).

Online adjuncts, in particular, face unique challenges related to institutional isolation and lack of engagement with full-time faculty. Virtual mentorship models, such as online mentoring communities, structured peer support, and interactive professional development workshops, have proven effective in improving online adjunct retention and engagement (Pearson & Kirby, 2018a; Puzziferro-Schnitzer & Kissinger, 2005). By offering dedicated mentoring programs for online faculty, institutions ensure equitable professional development opportunities for all faculty members, regardless of instructional modality (Pearson & Kirby, 2018b).

Building Sustainable Leadership Development for Chairs

Department chairs play a critical role in faculty leadership and institutional governance, yet many receive little formal preparation for their responsibilities. Structured mentorship programs for department chairs help them develop strategic leadership skills, operational efficiencies, and faculty support strategies (Pillar, 2025).

Mentorship constellations provide peer networks for department chairs, allowing them to learn from experienced leaders and gain insights into effective administrative practices (Vandermaas-Peeler & Moore, 2023). Reverse mentoring also plays a role in leadership development, as chairs benefit from early-career faculty perspectives on student engagement, emerging pedagogies, and institutional challenges (Seeing Behind the Curtain, Cain et al., 2024).

By incorporating mentorship into department chair training and leadership development programs, institutions strengthen faculty leadership pipelines and promote long-term institutional stability (Hope Circuits, Riddell, 2024).

Final Thoughts

Structured, generative mentorship is essential for faculty development, retention, and leadership sustainability. By embracing mentorship constellations and reverse mentoring, institutions can build dynamic faculty support networks that foster continuous learning, collaboration, and professional growth.

Mentorship programs should be intentional, incentivized, and embedded in faculty development initiatives, ensuring that adjuncts, department chairs, and early-career faculty receive the support and guidance necessary for long-term success (Vandermaas-Peeler & Moore, 2023).

By prioritizing mentorship as a core institutional value, higher education institutions can create inclusive, engaged faculty communities that drive academic excellence and student success. The principles outlined in Hope Circuits (Riddell, 2024) underscore the need for systemic mentorship ecosystems that cultivate resilience, adaptability, and institutional belonging—ensuring that faculty at all levels thrive in an evolving academic landscape.

References

AFT. (2022). State of adjunct faculty in higher education. American Federation of Teachers.

Cain, L., Goldring, J., & Westall, A. (2024). Seeing behind the curtain: Reverse mentoring within the higher education landscape. Teaching in Higher Education, 29(5), 1267-1282. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2022.2129963

Defining Mentoring. (2024). Mentoring in meaningful relationships. Elon University. https://www.elon.edu/u/mentoring-relationships/ace-report/defining-mentoring/

Faculty Focus. (2024). An online mentoring model that works. Faculty Focus. https://www.facultyfocus.com/articles/online-education/an-online-mentoring-model-that-works/

Gibson, A., & O’Keefe, P. (2019). Faculty development and adjunct faculty success. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, 41(3), 233-249. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360080X.2019.1569234

How Reverse Mentoring Helps Co-Create Institutional Knowledge. (2024). THE Campus: Learn, Share, Connect. https://www.timeshighereducation.com/campus/how-reverse-mentoring-helps-cocreate-institutional-knowledge

Mentoring Constellations in Global Contexts. (2024). Center for Engaged Learning. https://www.centerforengagedlearning.org/mentoring-constellations-in-global-contexts/

O’Connor, R., Barraclough, L., Gleadall, S., & Walker, L. (2025). Institutional reverse mentoring: Bridging the student/leadership gap. British Educational Research Journal, 51(1), 344-368. https://doi.org/10.1080/01411926.2025.009475

OpenAI’s DALL-E. (2025). Conceptual illustration of Beyond the Tenure Track: How Generative Mentoring of Adjunct Faculty and Department Chairs Enhances Institutional Quality and Student Success [AI-generated image]. Retrieved from https://labs.openai.com

Pearson, M. J., & Kirby, E. G. (2018a). An online mentoring model that works. Faculty Focus. https://www.facultyfocus.com/articles/online-education/an-online-mentoring-model-that-works/

Pearson, M. J., & Kirby, E. G. (2018b). Best practices for training and retaining online adjunct faculty. Magna Publications. https:// www.facultyfocus.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/Best-Practices-for-Training-and-Retaining-Online-Adjunct-Faculty.pdf

Pillar, G. (2025). From margins to mainstream: Elevating adjunct faculty for academic excellence. Innovative Higher Education Professional.

Pillar, G. (2025). The unsung leaders: Navigating department chair responsibilities at smaller private institutions. Innovative Higher Education Professional.

Puzziferro-Schnitzer, M., & Kissinger, J. (2005). Supporting online adjunct faculty: A virtual mentoring program. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 9(2), 39-42. https://doi.org/10.24059/olj.v9i2.1785

Research Overview. (2024). Center for Engaged Learning. https://www.centerforengagedlearning.org/mentoring-matters/research-overview/

Riddell, J. (2024). Hope circuits: Rewiring academia for resilience and transformation. University Press.

Seeing Behind the Curtain. (2024). Reverse mentoring within the higher education landscape. Teaching in Higher Education. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2022.2129963

Vandermaas-Peeler, M., & Moore, J. L. (2023). Mentoring constellations in global contexts: A new framework for faculty development. Center for Engaged Learning.

Zarrow, S. E. (2018, August 23). How tenured and tenure-track faculty can support adjuncts (opinion). Inside Higher Ed. Retrieved from