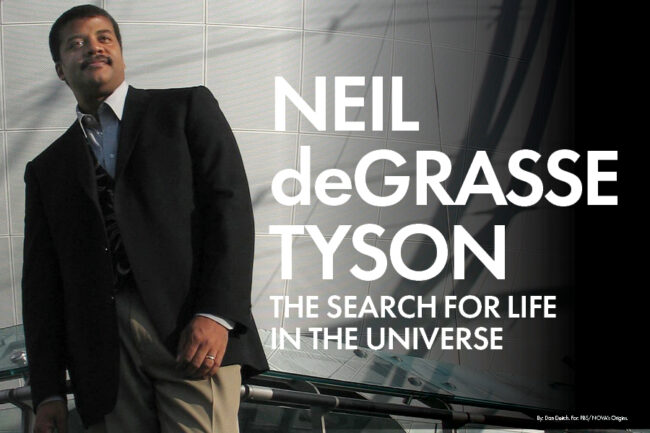

Last night I listened to Neil deGrasse Tyson hold a sold-out audience for two hours with a mix of humor, data, and wonder. As a scientist myself, I’ve always admired his ability to make complex ideas feel both rigorous and accessible. What struck me most wasn’t the astronomy; it was the mindset. Tyson described how the discovery of exoplanets, planets orbiting stars beyond our own, reshaped how scientists search for life in the universe. That same mindset, I realized, is exactly what higher education needs as we search for signs of learning in the modern era.

Curiosity Before Certainty

When the first exoplanet was discovered in 1995, the number of confirmed worlds beyond our solar system was zero. Today, there are more than 6,000. Each was found not by chance, but by curiosity paired with persistence. Scientists didn’t begin with certainty; they began with questions, models, and the humility to be wrong. That’s the essence of the Exoplanet Mindset: stay curious, refine your instruments, and look again.

For higher education, curiosity must come before certainty, too. Our “instruments” may be assessment tools, surveys, or enrollment dashboards, but the spirit is the same. When something isn’t working—a course, a program, a policy—our instinct shouldn’t be to defend the model. It should be to recalibrate, to look again, to search for new signals of success that may lie just beyond our usual field of view.

Generation Exoplanet Meets Generation Modern Learner

Tyson jokingly called those born after 1995 “Generation Exoplanet”, a generation that has always known the universe to be bigger than we once imagined. In higher ed, I think of today’s students as Generation Modern Learner. They, too, inhabit a landscape larger than what our systems were designed for. Their world includes hybrid work, digital credentials, side hustles, and constant connectivity. They expect responsiveness, relevance, and respect for the many ways they learn and live.

Just as astrophysicists had to redesign their instruments to detect worlds they couldn’t see, institutions have to redesign policies, classrooms, and support systems to recognize learners we don’t always understand. Modern Learner Success depends on the same combination of creativity and discipline that drives discovery in science, imagining what could exist, then building the tools to prove (or disprove) it.

Grounded in Data…. But Realistic About the Limits

Tyson reminded the audience that exoplanet research advanced because scientists learned to detect minute changes in starlight, drops in brightness so small they seemed almost impossible to measure. Progress came through data, not declarations.

In higher education, we talk often about being data-driven, and that’s a good thing. But here’s the caveat: sometimes, the data simply doesn’t exist yet. We may not have robust evidence about how a new initiative will perform, or how a pilot program will impact student belonging. Leadership means balancing the discipline of data with the courage of judgment. As in science, we can’t let the absence of perfect data become an excuse for inaction. Sometimes, you have to launch the telescope before you know exactly what you’ll find.

From Discovery to Design

What I find most inspiring about the exoplanet story is that it’s not really about planets, it’s about people. It’s about the relentless drive to understand, to test, to share, and to refine. Tyson has spent decades translating that spirit for the public, showing that science isn’t a collection of facts, it’s a process of disciplined wonder.

That same process belongs in every provost’s office, every faculty meeting, and every strategic plan. When we approach the modern learner with the Exoplanet Mindset, we stop asking only what’s broken and start asking what new forms of life, new ways of learning, belonging, and thriving, might already be there, waiting to be seen.

Final Thoughts

Tyson once said that science makes us better shepherds of civilization. I think higher education can (and should) do the same, if we remember that discovery isn’t just a scientific act, it’s a human one. Every student we serve is their own uncharted world. Our task is to keep searching the skies.