Teaching to Ghosts: How Higher Ed’s Past Haunts Us—and What It Takes to Move On

gregpillar

on

May 9, 2025

Title Image: OpenAI. (2025). Vibrant campus scene with a haunted building and a diverse mix of students, faculty, and staff interacting. DALL·E. https://openai.com/dall-e

The Ghosts in the Classroom

A professor sits down to design a syllabus. He—or she—imagines a student who is 18-19 years old, lives on campus, attends class full time, and has long afternoons to read, reflect, and write. The course is built around that student—the one we used to picture when we talked about “college.”

There are students sitting in our classrooms who, by nearly every measure, are invisible. They show up—but not always at 8:00 a.m. and not always in person. They juggle coursework with caregiving, jobs, anxiety, trauma, or housing insecurity. Some are first-generation college students; others have stopped out and come back; many question whether they belong in the room at all. They are not who our systems were built for. And too often, they are treated as if they aren’t really there.

We have built an entire educational apparatus on a lingering myth: that today’s college student is academically prepared, economically secure, and fully devoted to full-time study, preferably in a residence hall surrounded by leafy quads. The problem is not that this student archetype never existed—it did, in pockets and privileged spaces. The problem is that we still organize our curriculum, advising, scheduling, and expectations around this idealized model while the real students before us live different, more complex realities (DeLaski, 2025; Selingo, 2025).

In reality, most college students today are navigating a landscape that looks nothing like the brochures. Nearly one-third have considered leaving their programs due to mental health, financial pressure, or lack of support (Gallup & Lumina Foundation, 2025). More than half of college students are employed while enrolled, and a significant number also serve as caregivers for siblings or elders (Goines, 2024). Many arrive underprepared—academically, emotionally, or logistically—not because they lack ability but because the system assumes a level of readiness that was never designed for them (ACT, 2023; Bookbinder, 2024).

And yet, our syllabi, our policies, and even our pedagogy often center expectations that belong to another era. We assign dense readings without accounting for digital reading habits or cognitive fatigue (Flaherty, 2024; Bookbinder, 2024). We demand synchronous attendance while students are working night shifts. We measure success by who fits the mold, not who grows beyond it. It’s not just that we are failing to serve these students—we’re haunting them with a version of college that serves only their ghosts.

If higher education is to be relevant—if it is to be just—it must confront this reality. We must meet students where they are, not where we wish they were. And that begins by seeing them clearly, not as ghosts in a traditional classroom fantasy, but as whole, capable, complex learners deserving of systems that believe in them.

The Myth of the “Traditional” Student

For decades, higher education has perpetuated a powerful illusion: the “traditional” student. This imagined learner is 18 to 22 years old, academically prepared, financially supported, attending full time, living on campus, and fully immersed in a four-year residential experience. That image still dominates campus brochures, administrative planning, and even faculty expectations. But it is largely a myth.

Today, only 26% of college students fit that profile—that is, students who are not only between the ages of 18 and 22 but who also attend full-time, live on campus, and are fully immersed in a four-year residential experience (DeLaski, 2025b; Hanover Research, 2025a). In terms of age alone, the student population is nearly split: 51.6% are age 20 or younger, while 48.4% are 21 or older. Notably, nearly 25% of students—3,956,430 individuals—are age 25 or older (National Student Clearinghouse Research Center, 2025). These figures highlight just how far removed our imagined “traditional” student is from the demographic reality on today’s campuses. And even among those who do fall within the traditional age range, many are working while pursuing their education. In 2020, 40% of full-time undergraduate students were employed, underscoring the fact that even traditional-aged, full-time students must often balance school with work responsibilities (National Center for Education Statistics, 2022).

Demographic projections make it even clearer: the pipeline of traditional-aged students is shrinking. National forecasts show declining high school graduation rates over the next decade, particularly in the Northeast and Midwest (Lane, et. al., 2024). This means that clinging to outdated models isn’t just inaccurate—it’s unsustainable.

Most students are older, work while enrolled, commute to campus or learn online, and are often the first in their families to attend college. Many are returning adults, veterans, parents, or students managing chronic health or mental health conditions. And yet, our institutional architecture—from advising models to course schedules to financial aid policies—continues to center the traditional student as the norm.

This mismatch creates what Jeff Selingo (2025) calls a “design lag”: a gap between who students are and the systems intended to serve them. It also creates deep frustration for faculty, who often try to teach in environments designed around the wrong assumptions. As one professor observed, “We are designing for ghosts”—a poignant critique of how higher education often caters to an outdated student archetype (Chappell, Natanel, & Wren, 2021).

The results are predictable. Underprepared students are treated as if they are anomalies. Working learners are seen as disengaged. Students who can’t attend every synchronous session are flagged as unreliable. These assumptions not only fail to support today’s students—they actively alienate them (Gallup & Lumina Foundation, 2025; ACT, 2023).

We need to retire the myth. Not just in our messaging, but in our policies, pedagogies, and priorities. The modern student is not a deviation from the norm. They are the norm. And when we continue designing around outdated ideals, we send a clear signal: this place was not built for you.

Meet the New Majority: The Modern Learner

Today’s students are not anomalies or outliers. They are the new majority—and they are reshaping the fabric of higher education. These learners are more diverse, more digitally immersed, more economically stretched, and more purpose-driven than the traditional students our systems were designed to serve.

They prioritize flexibility and accessibility over legacy academic experiences defined by geographic location or institutional prestige. Instead of waiting for brochures, they evaluate institutions based on transparency, adaptability, and outcomes. Nearly 70% use AI tools like ChatGPT to research colleges, and they build personalized pathways informed by real-time information and real-world goals (EducationDynamics, 2025).

Balancing coursework with caregiving, job responsibilities, and family support is routine—not exceptional. Even those within the traditional age band are navigating competing pressures that once defined “nontraditional” status. What unites this student population is not age or format, but intent: they are seeking learning that fits their lives. Modular learning options, career-aligned credentials, and asynchronous access aren’t bonus features—they are the new baseline (Sallustio & Colbert, 2024; Hanover Research, 2025a).

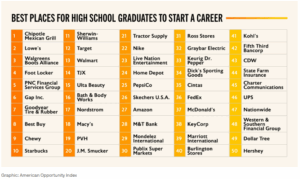

Institutions that deliver short-term, stackable credentials connected to in-demand skills are not just innovating—they are surviving. These learners want to know how their education connects to careers, not only someday, but now. High-impact career services that integrate early and often, rather than waiting until senior year, are vital. Effective models build relationships with industry, empower faculty partnerships, and make employability a shared responsibility across the institution (Hanover Research, 2023).

Modern students are also clear-eyed about value. They don’t need platitudes about lifelong learning. They want to see return on investment through tangible opportunities, relevant coursework, and pathways to economic mobility. Messaging must move beyond romanticized campus experiences to a clear articulation of purpose, fit, and impact (Hanover, 2025b).

To retain this new majority, institutions must also recognize the risk of attrition—especially for those navigating instability or trauma. Targeted support strategies like early alert systems, proactive advising, and embedded academic coaching are not perks—they are survival infrastructure (Hanover Research, 2019).

This isn’t just about keeping students enrolled. It’s about honoring their time and trusting their goals. And that trust must extend to acknowledging that for some, a degree isn’t the only—or even best—path. High-quality, workforce-aligned credentials must be welcomed, not viewed as secondary options (Goines, 2024).

Kathleen DeLaski (2025b) calls this group “the new majority”—a diverse and growing student population too long treated as an exception. Designing for them means designing for everyone. It isn’t about lowering standards. It’s about raising relevance, deepening connection, and expanding access.

These students remain eager to learn, even as traditional systems often push them away. Survey data continue to show that interest in higher education remains strong, particularly among those seeking meaningful work, career growth, and personal fulfillment (Ray, 2025). Yet trust is fragile. Many students perceive a gap between what colleges promise and what they deliver—especially around value, affordability, and inclusion (Edge Research & HCM Strategists, 2024).

If we want to retain these learners—and truly serve them—we must rewire the student experience to reflect who they are. That means rethinking advising, communication, instructional design, support services, and faculty development to serve students whose time, attention, and trust must be earned anew.

Systems Built for Ghosts: Where Misalignment Happens

When our systems are built for students who no longer exist, misalignment isn’t just a policy problem—it becomes a daily obstacle. And for the modern learner, those obstacles accumulate fast.

Consider the curriculum. Many programs still assume a standard 15-credit-hour semester across four years, often locking students into rigid, sequential course paths that unravel with the slightest disruption. For students working 30 hours a week, raising children, or returning to college after time away, this structure makes success unnecessarily difficult (Laff & Carlson, 2022; EducationDynamics, 2025; Gallup & Lumina Foundation, 2025). “On time” becomes a myth; “full time” becomes a barrier.

These assumptions often extend into the classroom. Faculty regularly assign dense reading loads assuming students are prepared, focused, and experienced with long-form academic text. But research shows that many students—especially in open-access institutions—are struggling with foundational reading skills. Expectations for daily engagement with difficult texts, without scaffolding or digital support, can overwhelm even the most committed learners (Wolf Jr., 2025). This isn’t a question of rigor—it’s a question of readiness.

Advising models also fail to account for the complexity of students’ lives. Too often, advising is built around linear paths and static requirements, assuming a full-time residential student who proceeds through four years with few disruptions. But today’s learners need conversations that account for transfer credits, family responsibilities, career pivots, and mental health. Systems must adapt to the fluid nature of the student journey—or risk losing them altogether (Laff & Carlson, 2022).

Systems also overlook the fact that many students are entering college underprepared—not because of personal failure, but because of systemic gaps in K-12 education. One recent study found that over half of incoming students at many institutions are not ready for college-level coursework, yet we continue to teach as if they are (Butrymowicz, 2017). This readiness gap becomes an invisible barrier embedded into every policy that assumes prior preparation.

Policies around attendance, deadlines, and participation carry silent assumptions: that students are financially secure, trauma-free, and constantly connected. But many are navigating mental health struggles, caregiving roles, and unstable housing. Systems that don’t accommodate this aren’t neutral—they’re extractive. They punish students for not conforming to a model they were never meant to fit (Riddell, 2023; Gallup & Lumina Foundation, 2025; Flaherty, 2024).

Even support services like tutoring, mental health counseling, or career coaching are often hidden behind procedural barriers or limited hours. Technically available doesn’t mean functionally accessible. As outlined in The Connected College, these resources are often wrapped in an “invisibility cloak”—ineffective not by absence, but by poor design (Felix, 2021; Hanover Research, 2025).

In my own leadership experience, I’ve seen these gaps firsthand. A student working retail evenings missed a required synchronous online class. A caregiver missed advising deadlines due to unpredictable family obligations. A first-generation student struggled with assessments built around timed essays and fast recall—formats that rewarded familiarity over learning.

None of these students lacked ambition. They lacked alignment. This is the real systems problem higher education must confront. We are still designing for ghosts, and it’s the living learners in front of us who pay the price.

Why This Hurts Everyone: Equity, Engagement, and Belonging

Misalignment in higher education doesn’t just inconvenience students. It chips away at equity, erodes belonging, and breaks the trust that holds institutions together. When we teach to ghosts, we not only lose students—we lose the soul of our mission.

For students, the message is loud and clear: this place was not built for you. When systems consistently fail to see or support them, students internalize the dissonance. They feel unseen, undervalued, and unsupported. Nearly one-third have considered leaving their institution, citing stress, anxiety, financial pressures, and a lack of connection or support as leading reasons (Gallup & Lumina Foundation, 2025; Marken, 2025a; Marken, 2025b). The emotional toll of navigating institutions built around outdated expectations is real—and rising.

The pressure to perform within academic structures designed for a narrow archetype compounds the problem. Many students report feeling overwhelmed by dense, analog reading assignments, inflexible pacing, and assessments that privilege speed and recall over synthesis and application. Even some of the most elite, high-achieving students are struggling to engage with traditional college reading loads, suggesting that the issue is structural, not personal (Horowitch, 2024).

This disconnect is especially harmful for students from historically marginalized backgrounds. When first-generation students, students of color, or those managing trauma and caregiving responsibilities encounter rigid systems, they are more likely to disengage—not out of apathy, but exhaustion. The absence of flexible structures communicates that they were never the intended audience. This design-based exclusion becomes an equity issue in plain sight.

Faculty are not exempt from this erosion of connection. Many feel demoralized, caught between students’ complex needs and institutional systems that fail to adapt. The emotional weight of declining attendance, missed deadlines, and unspoken struggles often lands squarely on instructors, who feel unsupported and ineffective. As Riddell (2023) argues, coherence and care must be institutionalized—not improvised—if we hope to sustain the energy and purpose of educators. Despite skepticism about cost, the belief in higher education’s long-term value persists. Most students still see college as a worthwhile investment, even if they view tuition pricing as unfair—underscoring the tension between value and trust that institutions must navigate (Marken & Hrynowski, 2025).

There are solutions—but they require intentionality. Scalable, equity-minded practices like proactive advising, early alert systems, and relationship-rich engagement models can interrupt student attrition and restore connection when implemented as part of a broader commitment to student success (Hanover Research, 2019). These aren’t just strategies. They are signals of care, and they shape whether students and faculty feel seen.

If we want to retain trust, we must restore alignment—between values and actions, expectations and supports, systems and the humans they are supposed to serve.

Rewiring for the Real Student: What Needs to Change

The future of higher education will not be secured through slogans or marginal adjustments. If colleges and universities are to thrive—and, in some cases, survive—they must move from accommodating the modern learner to redesigning entirely around them. This is not a matter of preference. It’s a matter of institutional viability and educational justice.

To begin, institutions must embrace modular, flexible, stackable learning pathways. Today’s students need degrees and credentials that can bend with life—not break under it. Certificates should ladder into degrees. Degrees should be customizable. Skills should be portable. And learning must be available in formats that respect time, context, and learner agency (EducationDynamics, 2025; Sallustio & Colbert, 2024; Hanover Research, 2025).

Second, we must embed trauma-informed, relationship-rich practices into the very architecture of our institutions. This means rethinking course policies, advising structures, communication practices, and faculty development. It’s not enough to “add” support; we need to embed support as a design principle. My own work in trauma-informed leadership as well as that of Jessica Riddell has shown that when institutions lead with care, transparency, and shared agency, student engagement improves—and so does staff morale (Pillar, 2024; Riddell, 2023).

Third, we need to stop treating equity and belonging as supplemental initiatives. They are not programs. They are principles. Inclusive design must be baked into everything—from how syllabi are written, to how learning outcomes are assessed, to how feedback is delivered. As The Connected College makes clear, institutions that center empathy and belonging in their culture not only serve students better—they build resilience into their very foundation (Felix, 2021).

Fourth, institutional leaders must be bold enough to discontinue what no longer works. Some legacy programs, policies, and roles have outlived their relevance. We need courage to close outdated offerings, reallocate resources, and invest in interdisciplinary, career-connected programs that reflect current needs. This doesn’t mean abandoning tradition. It means honoring mission by updating methods.

One compelling example of this kind of bold redesign comes from Dr. Melik Peter Khoury, President of Unity Environmental University. Under his leadership, Unity transformed from a tuition-dependent college serving fewer than 500 students into a national institution serving nearly 10,000—without chasing prestige or abandoning mission. The transformation wasn’t cosmetic. It included a full overhaul of governance, curriculum, support structures, and faculty models—grounded in scalability, relevance, and student-centered design (Khoury, 2025). His approach makes clear that institutional reinvention isn’t about rebellion—it’s about responsibility. And it starts by refusing to replicate a system that no longer serves.

And finally, we need to rebuild trust. That begins with telling the truth—about who our students are, about what they need, and about what it will take to meet them. Trust grows when students see policies that reflect reality, hear language that honors their experiences, and encounter faculty and staff who are empowered to support them holistically.

This work is hard. But it is also hopeful. The ghost stories we tell ourselves—about what college used to be, or who deserves to be here—no longer serve us. What comes next must be built not on nostalgia, but on clarity, care, and courage.

Final Thoughts: Letting Go of Ghosts

Nothing I’ve written here is revolutionary. These ideas—the urgency to meet students where they are, the call to redesign outdated systems, the recognition of the modern learner—have been championed by many others, many of them with larger platforms, more influential audiences, and longer résumés. But that’s precisely why I’m adding my voice.

Because this message can’t be shared enough.

It bears repeating in every meeting, every convocation address, every policy review, every accreditation review, and every course redesign. As institutions grapple with enrollment declines, rising skepticism, financial strain, and even closures, the through line in many of their stories will be the same: they spent too long designing for a student who doesn’t exist anymore.

This article has made the case that higher education’s default systems—its curricula, policies, and assumptions—are no longer fit for purpose. We’ve seen how these misalignments compound barriers for today’s learners, demoralize educators, and undercut institutional trust. But we’ve also explored a path forward: one grounded in coherence, care, flexibility, and relevance.

The erosion of public trust in higher education is not accidental. In recent surveys, confidence in colleges and universities has reached historic lows, with fewer than half of Americans expressing strong faith in the sector (Jones, 2024). And yet, the desire for learning, growth, and opportunity remains high. People still believe in the promise—if not always the practice—of higher education.

This piece is just one contribution to a wider and growing conversation. Countless scholars, educators, and reformers have been urging change grounded in care, relevance, and equity (Pillar, 2024). What we need now is not more awareness—but more action.

The real student is here now. And they are watching to see whether we’re brave enough to see them.

Higher education doesn’t need more ghosts. It needs a reckoning—and the resolve to build what comes next

References

ACT. (2023). 2023 National ACT profile report. ACT. https://www.act.org/content/dam/act/unsecured/documents/2023-National-ACT-Profile-Report.pdf

Bookbinder, H. (2024). The average college student today. The Commonplace. https://hilariusbookbinder.substack.com/p/the-average-college-student-today

Butrymowicz, S. (2017, January 30). Most colleges enroll students who aren’t prepared for higher education. The Hechinger Report. https://hechingerreport.org/colleges-enroll-students-arent-prepared-higher-education/

Chappell, K., Natanel, K., & Wren, H. (2021). Letting the ghosts in: Re-designing HE teaching and learning through posthumanism. Teaching in Higher Education, 26(7–8), 968–984. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2021.1952563

DeLaski, K. (2025a, February 3). OPINION: It is time to expand the definition of college to include other high-quality pathways. The Hechinger Report. https://hechingerreport.org/opinion-we-must-acknowledge-that-students-are-asking-for-options-beyond-the-four-year-college-degree/

DeLaski, K. (2025b). Who needs college anymore? Imagining a future where degrees won’t matter. Harvard Education Press.

Edge Research & HCM Strategists. (2024, March 11). Student perceptions of American higher education. Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. https://usprogram.gatesfoundation.org/news-and-insights/articles/student-perceptions-of-american-higher-education

EducationDynamics. (2025). Engaging the modern learner: 2025 report on the preferences and behaviors shaping higher ed. https://tinyurl.com/539upxm4

Felix, E. (2021). The connected college: Leadership Strategies for Student Success. ThriveU Press

Flaherty, C. (2024, March 15). Is this the end of reading? The Chronicle of Higher Education. https://www.chronicle.com/article/is-this-the-end-of-reading

Gallup & Lumina Foundation. (2025). The state of higher education 2025. https://www.gallup.com/analytics/644939/state-of-higher-education.aspx

Goines, D. (2024, December 2). OPINION: Schools can and should do more to help students prepare for career paths that don’t require a college degree. The Hechinger Report. https://hechingerreport.org/opinion-our-system-steers-most-students-toward-attending-college-but-it-is-not-realistic-or-even-desirable-for-everyone/

Hanover Research. (2025a). 2025 trends in higher education. Hanover Research.

Hanover Research. (2025b). Communicating the value of a college degree. Hanover Research.

Hanover Research. (2025c). Microcredential Trends 2025. Hanover Research.

Hanover Research. (2023). Benchmarking best-in-class career services. Hanover Research.

Hanover Research. (2019). Prevent student dropout toolkit. Hanover Research.

Horowitch, R. (2024, November). The elite college students who can’t read books. The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2024/11/the-elite-college-students-who-cant-read-books/679945/

Jones, J. M. (2024, July 8). U.S. confidence in higher education now closely divided. Gallup. https://news.gallup.com/poll/646880/confidence-higher-education-closely-divided.aspx

Khoury, M. P. (2025, May 9). I wasn’t meant to lead their system. I was meant to reimagine it. LinkedIn. https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/i-wasnt-meant-lead-system-reimagine-dr-melik-peter-khoury-0zale/?trackingId=fbeez7km13b%2FNp7h3ABJDw%3D%3D

Laff, N. S., & Carlson, S. (2022). Hacking college: Why the Major Doesn’t Matter – and What Really Does. Johns Hopkins University Press

Lane, P., Falkenstern, C., & Bransberger, P. (2024). Knocking at the College Door: Projections of High School Graduates. Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education. https://www.wiche.edu/knocking.

Marken, S. (2025a, May 1). One in three college students consider leaving program. Gallup. https://news.gallup.com/poll/659897/one-three-college-students-consider-leaving-program.aspx

Marken, S. (2025b, March 26). Mental health, stress top reasons students consider leaving. Gallup. https://news.gallup.com/poll/644645/mental-health-stress-top-reasons-students-consider-leaving.aspx

Marken, S., & Hrynowski, Z. (2025, February 15). College prices seen as unfair but worth the investment. Gallup. https://news.gallup.com/poll/657686/college-prices-seen-unfair-worth-investment.aspx

National Center for Education Statistics. (2022). Student employment (SSA indicator). https://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/indicator/ssa

National Student Clearinghouse Research Center. (2025). Current term enrollment estimates – Spring 2025. https://nscresearchcenter.org/current-term-enrollment-estimates/

Pillar, G. (2024). Beyond the critique: A nuanced approach to higher education reform for the modern learner. GregPillar.com. https://gregpillar.com/beyond-the-critique-a-nuanced-approach-to-higher-education-reform-for-the-modern-learner/

Pillar, G. (2024). Building resilient leadership in higher education: Merging trauma-informed practices with key presidential competencies. GregPillar.com. https://gregpillar.com/building-resilient-leadership-in-higher-education-merging-trauma-informed-practices-with-key-presidential-competencies/

Ray, J. (2025, May 7). Interest in higher education remains high. Gallup. https://news.gallup.com/poll/660134/interest-higher-education-remains-high.aspx

Riddell, J. (2023). Hope circuits: Rewiring Universities and Other Organizations for Human Flourishing. McGill-Queen’s University Press

Selingo, J. (2025). The state of higher education 2025, jeffselingo.com

Sallustio, J., and K. Colbert. (2024). Engaging the modern learner in higher education: Strategies for educators. https://evolllution.com/engaging-the-modern-learner-in-higher-education-strategies-for-educators

Wolf, F. A., Jr. (2025, January 17). Help college students read: Gen Z can’t make it through a book. Professors can help. The James G. Martin Center for Academic Renewal. https://jamesgmartin.center/2025/02/help-college-students-read/

About 10 years ago Charlotte found itself in an undesirable position due to a

About 10 years ago Charlotte found itself in an undesirable position due to a