The Future of College Majors: Reinvention or Extinction? —— Part 2: Beyond Declining Enrollments: Creating Adaptive, Interdisciplinary Programs for the Modern Student

gregpillar

on

March 7, 2025

The challenge facing higher education is not merely about deciding which programs to add or cut—it is about reimagining how academic offerings should evolve to better serve students, institutions, and the workforce. Traditional majors, particularly those in the humanities and some social sciences, are experiencing significant declines in enrollment, leading institutions to consider program closures. The declines are due, in part, to there being no clear connection to gainful employment after graduation. The value of certain majors and liberal arts degrees simply to be “well rounded” and “educated citizens” is in itself, not sufficient. However, eliminating struggling programs without rethinking how disciplines can be integrated into new, dynamic, and skill-based curricula is shortsighted.

Rather than outright elimination, universities have the opportunity to transform their academic structures, making them more interdisciplinary, flexible, and aligned with labor market demands. This shift is not only relevant for the humanities but also crucial for STEM, business, health, and other fields that increasingly intersect with technology, policy, and ethics (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2022). The most resilient academic programs will be those that foster adaptability, problem-solving, and cross-disciplinary collaboration, preparing students for evolving career landscapes rather than static job markets.

As institutions explore academic transformation, it is essential to differentiate between interdisciplinary and multidisciplinary approaches, as well as between interdisciplinary majors and interdisciplinary studies as a degree completion route. Interdisciplinary programs intentionally integrate multiple fields of study, synthesizing knowledge and methodologies to create a cohesive, problem-solving framework. In contrast, multidisciplinary programs draw on multiple disciplines but do so without fully integrating or synthesizing them. While multidisciplinary studies place various academic fields under a thematic umbrella, they often function independently, lacking the deep connections that define true interdisciplinary education.

A related concept gaining traction in research and policy discussions is convergence research, a term championed by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine and the National Science Foundation (NSF). The National Academies define convergence research as “a comprehensive synthetic framework for tackling scientific and societal challenges that exist at the interface of multiple fields. By merging these diverse areas of expertise in a network of partnerships, convergence stimulates innovation from basic science discovery to translational application” (National Research Council, 2014, p. 3). While interdisciplinary education integrates fields, convergence represents the next step—one that fosters deep, solution-oriented collaboration between disciplines. Bringing interdisciplinary and multidisciplinary together. Thus, an effective interdisciplinary education should not merely introduce students to multiple disciplines and facilitate integration, but should go further to cultivate convergence skills—the ability to synthesize knowledge, methodologies, and practical experience across fields to address complex challenges.

The concept of convergence also broadens the definition of education beyond the traditional classroom experience. In this context, “education” refers to the totality of a student’s learning journey—spanning coursework, research, internships, service-learning, and co-curricular experiences. A well-designed interdisciplinary program should provide students with opportunities to apply their learning across diverse contexts, reinforcing convergence skills in ways that prepare them for dynamic, evolving careers.

Many institutions offer an Interdisciplinary Studies degree as a flexible degree completion option for students who have accumulated credits across multiple disciplines and need a structured pathway to graduation (Mazzoni, J. F. R., 2024). While this model provides an important avenue for degree attainment, it differs from intentionally designed interdisciplinary programs that integrate multiple fields from the outset. The recent book Hacking College by Ned Laff and Scott Carlson introduces the concept of Field of Study, which encourages students to center their college experience around a “wicked multidisciplinary problem” of deep personal and societal relevance (Laff & Carlson, 2025). This model moves beyond traditional academic structures by allowing students to craft learning experiences that connect disparate fields into meaningful and applicable frameworks.

The Field of Study concept aligns with the broader movement toward interdisciplinary majors that are intentionally structured around integration. Programs such as Bioethics & Artificial Intelligence, Health & Data Analytics, or Environmental Policy & Business exemplify this shift—combining knowledge from multiple domains into new, cohesive areas of study that reflect the complexity of real-world issues. These interdisciplinary programs are designed to equip students with both depth and breadth, helping them navigate the increasingly interconnected workforce.

Additionally, Hacking College critiques the rigid, bureaucratic nature of many higher education pathways, arguing that students are often forced to navigate a series of institutional hurdles rather than engaging in a genuinely transformative intellectual and professional journey (Laff & Carlson, 2025). The book highlights the need for students to build their own pathways—ones that integrate multiple disciplines while fostering intellectual curiosity, emotional growth, and career preparation. This underscores the importance of developing interdisciplinary majors that not only reflect workforce demands but also empower students to take ownership of their education.

The next sections explore how institutions can break down academic silos, implement interdisciplinary programs, and reimagine advising to better support student-driven, flexible learning models that cultivate convergence skills and prepare students for the future.

The Interdisciplinary Imperative: Breaking Down Academic Silos

Interdisciplinary programs are increasingly recognized as a viable alternative to declining standalone majors. Employers value graduates who can synthesize knowledge across disciplines, adapt to emerging challenges, and apply critical thinking to real-world problems (Spelt et al., 2023). While traditional majors have historically operated within rigid academic silos, modern workforce demands necessitate a shift toward more integrative and skill-based curricula.

For smaller institutions, the urgency of this transformation is particularly acute. Low-enrollment programs can become financial liabilities, stretching faculty resources and administrative costs without generating sustainable returns. Interdisciplinary programs provide a strategic pathway to consolidate struggling majors while maintaining a breadth of academic offerings that prepare students for dynamic careers. Importantly, restructuring programs does not inherently require faculty layoffs but rather a rethinking of faculty roles, workload distribution, and course integration. Faculty members who previously specialized in single-discipline programs can transition into interdisciplinary teaching and research roles, ensuring that their expertise continues to enrich the institution in new and relevant ways.

One approach that has gained traction is allowing students to design their own interdisciplinary majors. At institutions like Lycoming College and Davidson College, students who demonstrate a clear academic vision can craft their own interdisciplinary programs by combining courses from multiple departments under faculty mentorship (Lycoming College, 2025). For example, at Davidson College, the Environmental Studies major initially began as a student-designed program before evolving into an established interdisciplinary major. These student-driven models provide flexibility for learners while allowing institutions to test the viability of new interdisciplinary fields before formally adopting them. When designed with faculty oversight, these programs maintain academic rigor while giving students agency over their education (Mazzoni, 2024).

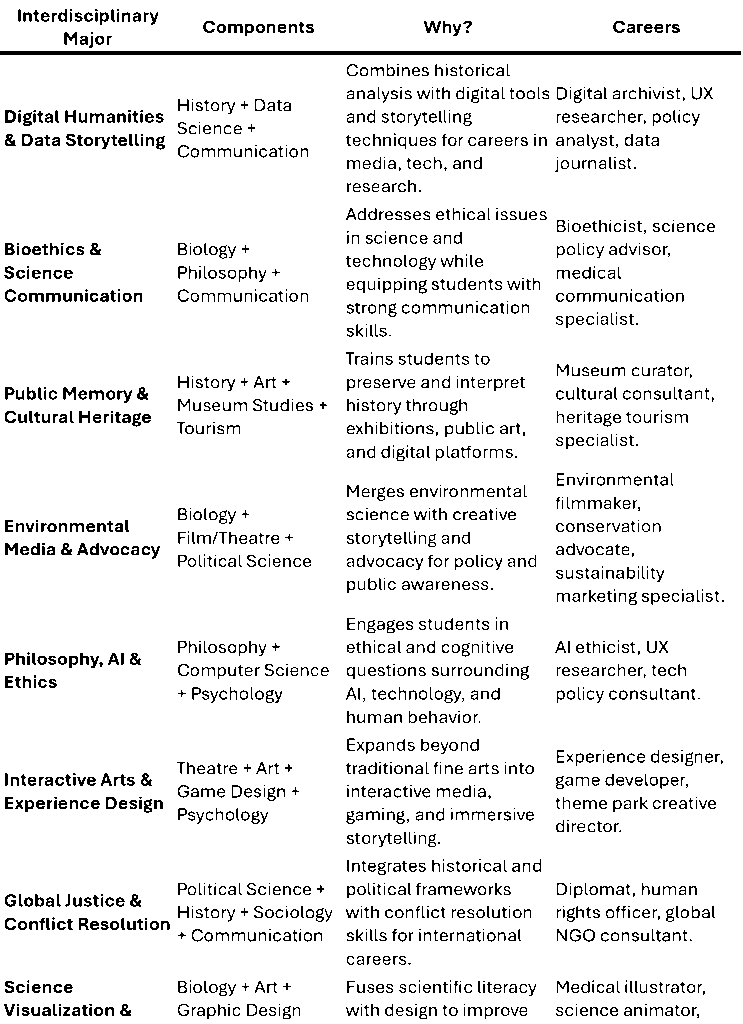

The table below presents examples of possible interdisciplinary programs that reflect labor market needs while promoting academic sustainability:

While these examples highlight the versatility of interdisciplinary education, institutions must also be cautious about creating overly specific programs that lack flexibility. A notable example is the forensic science degree boom of the early 2000s. Fueled by television dramas like CSI and NCIS, many universities introduced forensic science programs to meet surging student interest. While these degrees provided direct career pathways, they often lacked the adaptability of traditional biology, chemistry, or physics degrees, which could have prepared students for forensic careers while offering broader employment opportunities (Dempsey, 2025). This underscores the importance of designing interdisciplinary programs that maintain adaptability, ensuring graduates can pivot into multiple career pathways rather than being locked into narrowly defined roles.

At Arizona State University, degree programs are structured around “knowledge enterprises,” which emphasize broad academic clusters rather than traditional departments (Crow & Dabars, 2023). Similarly, Northeastern University has integrated experiential learning with interdisciplinary coursework, allowing students to gain both academic and practical expertise in high-demand sectors. These institutional models demonstrate that universities can redesign their academic portfolios without compromising intellectual rigor, making graduates more competitive in a rapidly changing job market.

Yet, as Hacking College notes, even in institutions that offer interdisciplinary pathways, students often face barriers in understanding how to navigate these options effectively (Laff & Carlson, 2025). Academic and career advising must evolve to support interdisciplinary exploration, ensuring that students are not just aware of new program structures but also equipped to take full advantage of them. Without proactive advising, students may struggle to see the value of interdisciplinary study or how to translate it into career opportunities.

The next section explores how institutions can overhaul advising and career development to align with interdisciplinary learning, ensuring students have the guidance and resources needed to craft meaningful, career-ready academic experiences.

Overhauling Advising and Career Pathways

A critical barrier to implementing interdisciplinary education is the outdated nature of academic and career advising. Traditional advising structures often emphasize course selection within rigid degree pathways rather than guiding students in crafting meaningful, cross-disciplinary learning experiences (Palmer, 2024). Hacking College argues that students need advising models that empower them to build an individualized college-to-career trajectory—one that embraces interdisciplinarity and intellectual curiosity rather than functioning as a bureaucratic checklist (Alssid & Lemoyne, 2025; Laff & Carlson, 2025). This rigid system often fails to equip students with the flexibility and skills necessary to navigate an increasingly dynamic job market (Ledwith, 2014).

Current advising models frequently separate academic and career advising into distinct functions, often providing generic guidance rather than individualized, skill-based mentorship (Parrent, 2023). The Work Forces podcast interview with Julian Alston and Caitlin Lemoyne highlights the need for a fundamental overhaul, suggesting that advising should focus on helping students develop hidden intellectualism by identifying the intersections between their academic interests and career goals (Alston & Lemoyne, 2025). Rather than funneling students into rigid degree tracks, advising should equip them with tools to translate interdisciplinary knowledge into actionable career pathways—a skill often missing in traditional advising models. Rey (2022) similarly emphasizes that primary-role academic advisers frequently lack the training or institutional support to provide integrated career advising, which contributes to students’ confusion about how to apply their education in the workforce.

One potential model for improving advising is integrating “Field of Study” pathways, in which students choose a central interdisciplinary theme or complex problem as the focal point of their education (Alssid & Lemoyne, 2025; Laff & Carlson, 2025). For example, rather than pursuing a conventional political science degree, a student might structure their studies around Global Conflict & Technology, integrating coursework from political science, cybersecurity, and media studies. Advising would then be tailored to support this individualized path, connecting students with relevant faculty, research opportunities, and industry networks. Laff and Carlson (2025) argue that this model helps students build social and cultural capital, which are crucial for navigating both academic and professional environments. The New Directions for Student Services report similarly advocates for a more collaborative approach between academic and career advising, ensuring that students develop not only academic competencies but also marketable skills that align with their career aspirations (Ledwith, 2014).

Advising must also reflect the realities of the modern workforce, particularly the rise of hidden jobs—career opportunities that are not easily accessible through traditional job-search methods (Laff & Carlson, 2025). The Work Forces podcast discusses how many institutions fail to prepare students for these hidden job markets, where professional networks, transferable skills, and interdisciplinary competencies determine career success (Alston & Lemoyne, 2025). Parrent (2023) reinforces this concern, noting that academic advising has historically functioned as an administrative checkpoint rather than a holistic framework for skill development. Effective advising should actively connect students with industry professionals, internship opportunities, and real-world projects that expose them to emerging fields rather than solely relying on predefined career tracks.

Furthermore, institutions should ensure that advising centers provide clear guidance on how interdisciplinary certificates and micro-credentials can supplement students’ primary degree programs. By embedding stackable micro-credentials into advising frameworks, universities can help students strategically build expertise in high-demand skills such as data analytics, communication, and leadership—regardless of their major (Spelt et al., 2009). These credentials not only improve employability but also allow students to customize their education without delaying graduation. For adult learners and those with some college, no credential (SCNC) status, micro-credentials can serve as jump-start mechanisms for degree completion or career advancement (McCartney & Daniels, 2024; Palmer, 2024). Programs that offer credit for prior learning (CPL) or competency-based education (CBE) ensure that these students gain recognition for their existing skills, further increasing accessibility and affordability (Welding, 2024).

Bridle et al. (2013) highlight the importance of preparing students for an interdisciplinary future by ensuring that advising frameworks emphasize adaptability and cross-sector competencies. Without intentional advising structures that integrate interdisciplinary coursework, experiential learning, and career preparation, students risk graduating with theoretical knowledge but without the practical skills necessary to navigate a rapidly changing job market.

The Harvard EdCast podcast reinforces these themes, arguing that institutions must redefine advising as an iterative, student-centered process rather than a one-time consultation about graduation requirements (Anderson, K., 2023). Effective advising should integrate academic interests, skill-building, and career preparation into a cohesive strategy that evolves throughout a student’s college experience. Without such proactive advising, students may struggle to see the value of interdisciplinary study or how to translate their education into viable career opportunities.

Ultimately, universities that fail to adapt their advising models to accommodate interdisciplinary and student-driven learning risk leaving students underprepared for an evolving job market. A transformed advising approach—one that prioritizes interdisciplinary learning, career integration, and real-world application—will be essential in ensuring that students make the most of their college experience while preparing for long-term professional success.

Interdisciplinary Certificates and Micro-Credentials: A Scalable Approach to Transformation

While interdisciplinary majors serve as a powerful mechanism for rethinking academic programs, they are not the only solution. Another viable approach is the expansion of interdisciplinary certificates and micro-credentials, which allow students to develop specialized competencies that enhance their degrees or serve as standalone credentials. These flexible learning pathways help students acquire in-demand, industry-specific skills while providing institutions with a cost-effective means to introduce interdisciplinary learning without the logistical challenges of launching new degree programs (Palmer, 2024; Stoddard et al., 2023).

Microcredentials are particularly valuable in fields where knowledge evolves rapidly, requiring graduates to integrate expertise from multiple disciplines. Emerging areas such as cybersecurity policy, health informatics, and climate data analytics illustrate how micro-credentials help bridge knowledge gaps across disciplines (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2022). For example, a Business & Sustainability certificate can equip business students with environmental policy insights, making them attractive to companies seeking corporate social responsibility expertise. Similarly, a Healthcare & Data Science certificate could prepare nursing or public health students to analyze big data trends in patient outcomes, enhancing their career prospects in health informatics (FIU College of Business, 2024).

Microcredentials as a Pathway for Degree Completion

One of the most significant benefits of microcredentials is their ability to serve as an on-ramp for adult learners and students with some college but no credential. Research from the Microcredentials Exploratory Pilot (McCartney & Terry, 2024) indicates that microcredentials provide a critical re-entry point for individuals who have paused their education due to financial, personal, or career-related barriers. By allowing these learners to gain immediate workforce-relevant skills, microcredentials serve as both a stepping stone to degree completion and a tool for career advancement.

For many adult learners, particularly those returning to college after time in the workforce, traditional degree pathways may feel daunting due to time constraints and financial pressures. However, when microcredentials are embedded within degree programs and structured as stackable credentials, they enable students to accumulate meaningful, credit-bearing learning experiences that can be applied toward an associate’s or bachelor’s degree (McCartney & Terry, 2024).

For example, a student working in healthcare who has completed a Public Health Leadership microcredential could apply those credits toward a Bachelor’s in Public Health. Likewise, a working professional who completes a Digital Marketing Analytics microcredential might later decide to pursue a degree in Business Administration with those credentials counting toward required coursework. By aligning microcredentials with broader degree frameworks, institutions can create flexible, modular learning opportunities that increase accessibility and degree completion rates among non-traditional students.

The Role of Credit for Prior Learning (CPL) and Competency-Based Education (CBE)

Microcredentials also play an essential role in Credit for Prior Learning (CPL) and Competency-Based Education (CBE) models, which validate a learner’s prior experience and skills to accelerate degree attainment. Many adult learners enter college with years of relevant work experience but lack formal credentials to demonstrate their expertise. CPL and CBE frameworks recognize this learning by assessing competencies rather than requiring students to repeat coursework in subjects they have already mastered (Stoddard et al., 2023).

For institutions, integrating microcredentials within CPL and CBE frameworks offers multiple advantages:

- It allows students to earn academic credit for industry-recognized credentials they have already obtained.

- It reduces time-to-degree, saving students money while improving retention and completion rates.

- It strengthens university-industry partnerships by aligning educational offerings with workforce needs.

Many universities, including Florida International University and Georgetown University, have already implemented interdisciplinary microcredential programs that connect to degree pathways, enabling students to gain recognized expertise while progressing toward graduation (FIU College of Business, 2024).

Stackable Microcredentials: Customization and Career Alignment

Beyond serving as standalone credentials, interdisciplinary micro-credentials can be designed to stack within undergraduate degree programs, allowing students to customize their academic paths. This approach ensures that students graduate with both broad foundational knowledge and specialized, career-relevant skills. Certain micro-credentials, such as Data Analytics, Leadership & Organizational Communication, and Global Studies, hold value across multiple disciplines and could be integrated within a variety of majors (Spelt et al., 2023).

For example:

- A biology major might complete a micro-credential in Data Analytics for Scientific Research, equipping them with computational skills that enhance their research capabilities.

- An English major could pair their degree with a UX Writing & Digital Media credential, preparing them for careers in digital communication.

- A political science major might pursue a Public Policy & Technology microcredential to strengthen their expertise in tech policy and governance.

By embedding stackable credentials within degree programs, universities can increase curricular flexibility while ensuring that students graduate with skills that are both field-specific and broadly transferable (Palmer, 2024). Stackability also benefits students by reducing time-to-degree and increasing employability. Rather than requiring students to take additional coursework after graduation to develop career-relevant skills, stackable micro-credentials allow students to build a more robust resume within their existing academic timeline (Crow & Dabars, 2023). Additionally, because micro-credentials can be industry-aligned, they provide immediate workforce value even before a student completes their full degree program.

Employer Recognition and Industry Partnerships

For microcredentials to be truly valuable, institutions must develop them in direct collaboration with employers to ensure they align with workforce needs. The Microcredentials Primer for Higher Education Leaders (Stoddard et al., 2023) highlights the growing employer preference for skills-based hiring, emphasizing that microcredentials are most effective when they are industry-recognized.

For example:

- Some universities partner with Google, IBM, and Microsoft to offer microcredentials in Cloud Computing, Cybersecurity, and AI Ethics, providing students with credentials that are directly valued by major employers.

- In healthcare, institutions have partnered with hospital networks to develop microcredentials in Health Informatics and Patient Advocacy, ensuring that graduates are well-prepared for evolving roles in the field (McCartney & Terry, 2024).

- In the public sector, microcredentials in Community Engagement & Public Administration have been co-developed with government agencies to equip students with essential policy and governance skills.

Building strong employer partnerships ensures that microcredentials translate into tangible career benefits, increasing job placement rates and strengthening institutional relationships with industries.

Financial Sustainability and Revenue Generation

For institutions, microcredentials represent not only an educational innovation but also a financial sustainability strategy. With declining traditional enrollments and growing financial pressures, universities are seeking alternative revenue streams that do not rely solely on full-degree tuition models. The Microcredentials Exploratory Pilot (McCartney & Terry, 2024) outlines how microcredentials provide institutions with:

- Increased student retention, as learners who see direct career value in their studies are more likely to persist to graduation.

- Greater curricular flexibility, as interdisciplinary microcredentials allow departments to collaborate without requiring full program overhauls.

- Improved alumni engagement, as microcredentials provide continuing education pathways that encourage lifelong learning.

By leveraging microcredentials as part of a comprehensive institutional strategy, universities can expand their reach to adult learners, increase degree completion rates, and generate additional revenue without overextending their existing faculty and administrative resources.

A Central Component of Higher Education’s Future

Interdisciplinary microcredentials and stackable certificates should not be viewed as supplemental to traditional degree programs but as integral components of higher education’s future. These programs offer scalable, flexible, and career-relevant learning opportunities that benefit both students and institutions.

By integrating microcredentials into degree pathways, expanding CPL and CBE opportunities, and partnering with industry leaders, universities can ensure that students graduate with the interdisciplinary, skill-based competencies necessary for today’s workforce. Institutions that embrace this transformation will be better positioned to serve both traditional and non-traditional learners while ensuring financial sustainability in an evolving educational landscape.

Restructuring Academic Departments: A More Holistic Approach

Beyond transforming individual programs, institutions must reconsider how academic departments are structured to foster interdisciplinary collaboration, reduce administrative inefficiencies, and align with workforce demands. The traditional department model—often rigidly divided by discipline—constrains cross-field engagement, limiting students’ ability to develop competencies that span multiple areas of expertise. As higher education evolves to meet complex global challenges, institutions that remain locked into outdated department structures risk falling behind (Crowley, Mustain, & Roberts, 2024).

Rigid departmental boundaries not only stifle innovation but also exacerbate financial and operational inefficiencies. At many institutions, low-enrollment programs remain siloed, forcing faculty to carry disproportionate service burdens while maintaining course offerings that attract only a handful of students each semester. This is particularly problematic for smaller colleges and tuition-dependent universities, where underperforming programs become significant financial liabilities (Gunsalus et al., 2023). By restructuring into broader interdisciplinary divisions or clusters, institutions can retain essential academic offerings while improving faculty workload distribution, streamlining administrative costs, and enhancing interdisciplinary collaboration (Anderson,K., 2023).

Alternative Models for Departmental Restructuring

To address these challenges, some universities have already restructured their academic departments into interdisciplinary knowledge clusters. Instead of being isolated in traditional disciplinary silos, faculty and students are organized into broad, problem-centered academic units that encourage cross-disciplinary engagement. Examples of emerging models include:

- Interdisciplinary Knowledge Clusters (Crowley, Mustain, & Roberts, 2024)

- Data & Society Division: Merging Computer Science, Digital Humanities, Public Policy, and Data Analytics to prepare students for careers in technology, government, and media.

- Health & Human Sciences Cluster: Combining Nursing, Public Health, Psychology, and Bioethics to encourage collaborative research and integrated approaches to healthcare challenges.

- Sustainability & Innovation Hub: Bringing together Environmental Science, Urban Planning, Business, and Sustainable Engineering to develop holistic solutions to climate change and resource management

- School-Based Models

- Some institutions have merged smaller, related departments into larger interdisciplinary schools, fostering cross-disciplinary collaboration while reducing administrative burdens.

- For example, rather than maintaining separate departments for journalism, communication, and digital media, universities can consolidate them into a School of Media and Information, allowing for more dynamic course offerings and shared faculty expertise (Anderson, K., 2023).

- Institutions such as the University of Washington’s College of the Environment and Georgia State University’s reorganized academic clusters demonstrate how restructuring enhances curricular flexibility and research collaboration while reducing redundancies (Drozdowski, 2024).

- Eliminating Standalone Departments Altogether

- Some institutions have replaced traditional departments with flexible, cross-disciplinary academic divisions, which encourage team-taught courses, shared faculty expertise, and adaptable degree pathways (Rosowsky & Keegan, 2020).

- By removing departmental barriers, universities increase interdisciplinary research collaboration and improve institutional agility in responding to workforce trends.

Addressing Faculty Concerns and Resistance

While restructuring offers clear benefits, institutional leaders must carefully navigate faculty concerns regarding disciplinary identity, job security, and teaching loads. Faculty members may fear that departmental mergers will diminish their academic field’s visibility or devalue their research expertise. Some may also be concerned that interdisciplinary teaching assignments will increase their workload without adequate institutional support (Gunsalus et al., 2023).

To address these concerns, universities must:

- Emphasize Faculty Inclusion in the Planning Process

- Institutions that engage faculty from the outset in designing new interdisciplinary structures are more likely to achieve faculty buy-in.

- Pilot programs, faculty task forces, and incentives for interdisciplinary research can help ensure that faculty play an active role in shaping the future of academic structures (Crowley, Mustain, & Roberts, 2024).

- Ensure That Faculty Retain Job Security and Research Opportunities

- Restructuring does not necessarily require faculty layoffs but rather a reorganization of teaching loads and research expectations.

- Faculty members can be repositioned into interdisciplinary teams, enabling them to apply their expertise in new, cross-disciplinary ways while maintaining their academic standing (Anderson, K, 2023).

- Institutions should offer faculty development programs that help professors transition into interdisciplinary teaching and research roles.

- Reduce Service Burdens Through Equitable Workload Distribution

- Faculty in small, low-enrollment departments often bear a disproportionate amount of service work, including committee participation and accreditation reporting.

- Merging these departments into larger interdisciplinary schools allows service responsibilities to be more evenly distributed, giving faculty more time for research, mentorship, and innovation (Blaylock, et. al., 2016).

Administrative & Operational Benefits of Restructuring

Beyond the academic benefits, restructuring optimizes institutional efficiency by:

✅ Reducing administrative redundancies – Merging departments into larger interdisciplinary schools consolidates administrative support, decreasing duplication of services (Anderson, K., 2023).

✅ Improving student experience – Interdisciplinary structures ensure students receive a more comprehensive education that aligns with industry trends and prepares them for a broader range of careers

✅ Streamlining governance structures – Fewer individual departments lead to more effective decision-making and faster curriculum adaptation to labor market changes (Gunsalus et al., 2023).

✅ Strengthening financial sustainability – By eliminating low-enrollment, high-cost standalone programs and consolidating faculty resources, institutions can reallocate funds to high-demand fields while still preserving disciplinary expertise (Crowley, Mustain, & Roberts, 2024).

Strategic Approaches for Implementing Restructuring

To ensure a successful transition, institutions should:

- Pilot restructuring efforts in select academic units before full implementation (Crowley, Mustain, & Roberts, 2024).

- Use institutional data (enrollment trends, workforce demand, and faculty workload analysis) to drive decision-making (Gunsalus et al., 2023).

- Engage faculty, students, and external stakeholders in the restructuring process to ensure new models align with both academic priorities and employer needs (Anderson, K., 2023).

- Provide clear transition plans for students enrolled in programs affected by restructuring, ensuring they can complete their degrees without disruption.

Restructuring academic departments is not just an administrative necessity—it is a strategic imperative for institutions seeking to improve academic innovation, interdisciplinary collaboration, and financial sustainability. Universities that embrace flexible, dynamic academic structures will be better equipped to navigate enrollment shifts, workforce transformations, and financial challenges in the years ahead.

By moving toward interdisciplinary clusters, school-based models, or fully integrated academic divisions, institutions can ensure that faculty thrive, students receive broad yet specialized training, and universities remain responsive to societal and labor market needs.

Final Thoughts: Making the Hard Choices – When Reinvention Isn’t Enough

Higher education must evolve beyond rigid disciplinary silos and outdated advising models if it hopes to meet the needs of modern learners and a changing workforce. The strategies outlined in this article provide institutions with a blueprint for transforming struggling majors, integrating interdisciplinary learning, and modernizing academic structures. Yet, while these approaches can reinvigorate many programs, reinvention is not always enough. Some academic programs will remain unsustainable due to persistently low enrollment, limited career pathways, or an inability to align with emerging interdisciplinary opportunities.

Institutions cannot afford to spread resources thinly across programs that no longer serve students or the institution’s long-term viability. Academic leaders must make data-driven, strategic decisions about which programs can be transformed and which must be phased out. This is not about indiscriminate cuts but about making intentional choices that strengthen institutional sustainability while ensuring that students receive high-quality, future-focused education.

How do institutions determine which programs can be saved and which should be discontinued? What strategies ensure that these decisions are made responsibly, equitably, and in alignment with institutional mission and financial sustainability? Part 3 of this series will address these questions, outlining a structured approach for evaluating academic programs, making tough but necessary decisions, and navigating the institutional and political complexities of academic realignment. The goal is not just to survive—but to ensure that institutions are positioned to thrive in an era of rapid change.

References

Alston, J., & Lemoyne, C. (2025, March 6). Scott Carlson & Ned Laff on Hacking College [Audio podcast episode]. In Work Forces. Retrieved from [https://www.workforces.info/podcast/episode/4a392bb2/scott-carlson-and-ned-laff-on-hacking-college]

Anderson, J. (2023). The future of academic restructuring: Lessons from leading institutions. Harvard EdCast.

Anderson, K. (2023, December 5). How an academic restructuring is creating interdisciplinary opportunities—and saving this university money. Inside Higher Ed. Retrieved from Inside Higher Ed

Bridle, H., Vrieling, A., Cardillo, M., Araya, Y., & Hinojosa, L. (2013). Preparing for an interdisciplinary future: A perspective from early-career researchers. Futures, 53, 22-32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.futures.2013.09.003​:contentReference[oaicite:3]{index=3}.

Blaylock, B., Zarankin, T. & Henderson, B. (2016). Restructuring Colleges in Higher Education around Learning. International HETL Review, Volume 6, Article 6, URL: https://www.hetl.org/restructuring-colleges-in-higher-education-around-learning

Crow, M. M., & Dabars, W. B. (2023). Designing the new American university. Johns Hopkins University Press.

Crowley, K., Mustain, M., & Roberts, J. (2024). Academic reorganization: How strategy drives structure. Presented at the 2024 Institute for Chief Academic Officers and Their Teams, Council of Independent Colleges.

Dempsey, S. (2025). Cross-disciplinary success: How interdisciplinary certificates are shaping the future. The Evolllution. Retrieved from https://evolllution.com/cross-disciplinary-success-how-interdisciplinary-certificates-are-shaping-the-future

Drozdowski, M. J. (2024, March 11). 7 challenges threatening the future of higher education. BestColleges. Retrieved from https://www.bestcolleges.com/news/analysis/7-challenges-threatening-future-of-higher-education/

FIU College of Business. (2024). The rise of interdisciplinary roles: STEM and business in the job market. Florida International University.

Gunsalus, C. K., Luckman, E. A., Ryder, J. J., & Burbules, N. C. (2023, November 29). Transforming challenged academic units. Inside Higher Ed. Retrieved from Inside Higher Ed

Laff, N. S., & Carlson, S. (2025). Hacking college: Rethinking what matters in higher education. Johns Hopkins University Press.

Ledwith, K. E. (2014). Academic advising and career services: A collaborative approach. New Directions for Student Services, 148(Winter), 49-62. https://doi.org/10.1002/ss.20108​:contentReference[oaicite:1]{index=1}.

Lycoming College. (2025). Interdisciplinary programs. Retrieved from https://www.lycoming.edu/interdisciplinary

Mazzoni, J. F. R. (2024, August 30). Interdisciplinary studies: Preparing students for a complex world. Faculty Focus. Retrieved from https://www.facultyfocus.com

McCartney, T., & Terry, B. (2024). Microcredentials exploratory pilot: Expanding access and career pathways through credential innovation. [White paper].

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2022). Imagining the future of undergraduate STEM education: Proceedings of a virtual symposium. The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/26314

National Research Council. (2014). Convergence: Facilitating transdisciplinary integration of life sciences, physical sciences, engineering, and beyond. The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/18722

OpenAI’s DALL-E. (2025). Conceptual illustration of Beyond Declining Enrollments: Creating Adaptive, Interdisciplinary Programs for the Modern Student [AI-generated image]. Retrieved from https://labs.openai.com

Palmer, K. (2024, January 23). Microcredentials on the rise, but not at colleges. Inside Higher Ed. Retrieved from https://www.insidehighered.com/news/tech-innovation/teaching-learning/2024/01/23/microcredentials-rise-not-colleges.

Parrent, C. (2023). Integrating career development into academic advising. National Career Development Association. Retrieved from NCDA.

Rey, B. (2022). Career advising from the primary role academic adviser’s viewpoint: A review of the literature. National Association of Colleges and Employers. Retrieved from NACE.

Rosowsky, D. V., & Keegan, B. (2020). What if there were no academic departments? Inside Higher Ed. Retrieved from Inside Higher Ed

Spelt, E. J., Biemans, H. J. A., Tobi, H., Luning, P. A., & Mulder, M. (2009). Teaching and learning in interdisciplinary higher education: A systematic review. Educational Psychological Review, Published Online, DOI 10.1007/s10648-009-9113-z

Stoddard, S., Nguyen, T., & Patel, R. (2023). Getting started with microcredentials: A primer for higher education leaders. Center for the Future of Higher Education and Talent Strategy, Northeastern University.

The Change Leader, Inc. (2024). Academic realignment and organizational redesign: Transforming institutions for the future of higher education. Retrieved from The Change Leader

Welding, L. (2024, July 11). The rise and future of microcredentials in higher education. BestColleges. Edited by J. Bryant. Fact-checked by M. Rose. Retrieved from https://www.bestcolleges.com/research/microcredentials-rise-in-higher-education/