Demystifying the value of a college degree—and what students and institutions can do to maximize it.

The College Cost Crisis

After more than 18 years working in higher education—and managing multi-million dollar budgets along the way—I confidently have a good understanding of how university finances operate (though there’s still a lot I’m learning every day). I keep an eye on the markets, but I don’t have the expertise—or the nerve—to be a day trader. And while I absolutely geek out over data, that’s usually in the world of environmental chemistry, not financial spreadsheets.

That said, I care deeply about helping students and families make informed choices—especially now, when those choices feel more complex than ever.

The question on a lot of people’s minds—parents, students, guidance counselors, and even policymakers—is whether college is still worth it. With tuition prices continuing to rise and student loan debt now exceeding $1.7 trillion, it’s a fair question. More people are also taking seriously the potential of other postsecondary paths—like trade schools, apprenticeships, or jumping directly into the workforce.

Those paths can absolutely offer a solid return—and often much faster than a four-year degree. For many, they lead to quicker employment, less debt, and a faster sense of financial stability. But over the long term, data still suggest that bachelor’s degree holders tend to have higher earning potential and greater economic and social mobility. In other words, short-term ROI might favor some non-college options, but the long-term payoff of a degree remains significant (Cheah, Van Der Werf, Morris, & Strohl, 2025; Cooper, 2024).

That said, not all degrees lead to high-paying jobs right away. Programs in fields like the humanities or education are often stigmatized for their lower starting salaries, but that doesn’t mean they lack value. Students who make the most of their college experience—by building transferable skills, seeking out applied learning opportunities, and staying open to diverse career paths—can often find rewarding work that leverages their degree in ways the statistics might not fully capture. Earning a degree in education, for example, doesn’t mean one must remain in the classroom forever. Likewise, a philosophy or English major might thrive in law, business, nonprofit leadership, or user experience design. Versatility, not just vocational training, is one of college’s greatest hidden returns.

Two of the most comprehensive national studies on college return on investment (ROI)—one from the Foundation for Research on Equal Opportunity (FREOPP), authored by Preston Cooper, and the other from Georgetown University’s Center on Education and the Workforce (CEW)—confirm that in most cases, a college degree yields strong financial returns over time (Cooper, 2024; Cheah et al., 2025). The catch is, those returns may take 10, 20, or even 30 years to fully materialize.

Meanwhile, students and families face steep up-front costs. Tuition, housing, books, and fees add up fast—and that’s before we even factor in loans and interest. Even if a degree pays off in the long run, the weight of debt and delayed earnings can make the ROI feel frustratingly out of reach in the early years.

And here’s an important point I want to emphasize: this isn’t just a conversation for traditional 18-year-olds entering college straight from high school. In fact, there are over 40 million adults in the U.S. with some college and no credential. For many of them, going back to school—whether for a certificate, associate’s, bachelor’s, or graduate degree—might be the key to unlocking better wages, job security, or new career paths. ROI matters to them, too.

So while I’m not a financial analyst, my goal in this article is to lay out the return on investment of college in plain terms—to give students, families, and adult learners alike a clearer picture of what they might gain, what it costs, and how long it takes to see the return. The stakes are high, and the timeline is long—but that doesn’t mean the investment isn’t worth it. It just means we need to understand it better.

Understanding ROI: What Do These Studies Measure?

If we’re going to talk seriously about the return on investment (ROI) of a college degree, we need to be clear about what that term actually means—and how researchers are measuring it. It turns out, there’s more than one way to calculate ROI, and the two most prominent studies in this space take slightly different approaches. Together, though, they offer a powerful window into how degrees pay off, for whom, and over what time horizon.

At its core, ROI in higher education is about comparing the cost of earning a credential with the financial benefit it provides over time. But just like in investing, the details matter. The FREOPP report, authored by Preston Cooper (2024), uses a comprehensive method that estimates the lifetime financial gain a student receives from completing a specific program—say, a bachelor’s in nursing at a private university—compared to what they likely would have earned had they entered the workforce directly out of high school. This model accounts for tuition costs, lost earnings during college, and the risk of non-completion.

The Georgetown Center on Education and the Workforce (CEW), by contrast, calculates institutional ROI based on cumulative post-enrollment earnings minus net price, using data from the U.S. Department of Education’s College Scorecard (Cheah, Van Der Werf, Morris, & Strohl, 2025). They present ROI over several timeframes: 10, 15, 20, 30, and 40 years after a student first enrolls. This allows them to show not just how much a degree pays off—but when. Their approach is intentionally conservative: they assume no income growth after year 10 and do not factor in debt repayment, which makes short-term ROI look even bleaker for students with loans.

Despite their differences, both studies reinforce a central truth: not all degrees offer the same financial payoff, and the path to ROI is rarely quick. For example, CEW finds that graduates of certificate and associate’s programs often see higher returns in the first 10–20 years because they enter the workforce sooner and with less debt. But over the long run, bachelor’s degrees tend to win out, with higher earnings compounding over time (Cheah et al., 2025). Similarly, the FREOPP report shows that what you study often matters more than where you study.

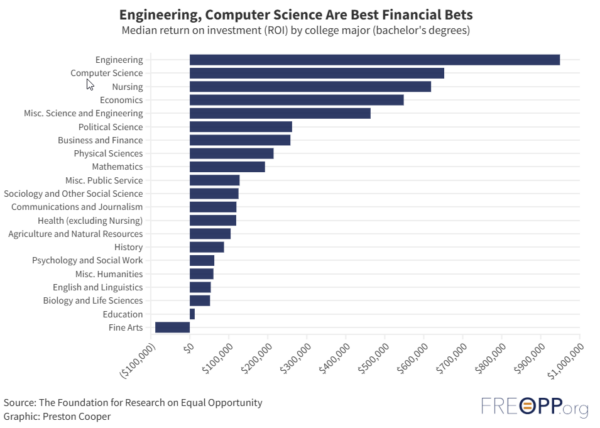

This is especially evident in FREOPP’s analysis of ROI by major. As shown below, students who earn degrees in engineering, computer science, economics, or nursing consistently realize the highest financial returns—regardless of institution. This further reinforces the point that field of study often drives ROI outcomes more than college brand.

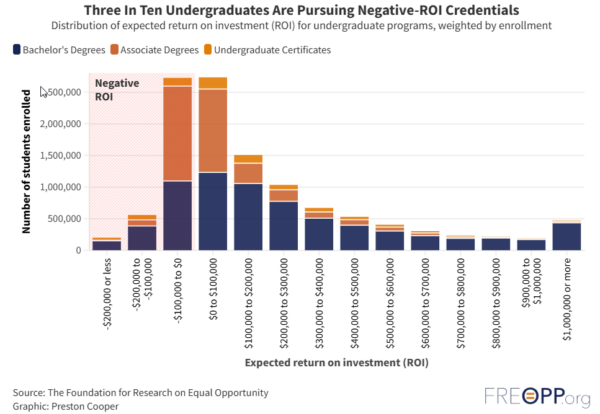

That’s why it’s especially concerning that nearly three in ten undergra duate students are currently pursuing programs with negative ROI. As this graph from the FREOPP report illustrates, far too many students are entering fields that are unlikely to pay off financially over time—a challenge that underscores the importance of access to program-level ROI data, high-quality advising, and career exploration support.

A bachelor’s in computer science or nursing typically yields a high ROI regardless of the institution, while degrees in performing arts, psychology, or some education programs often result in a net financial loss—even at prestigious universities (Cooper, 2024).

That said, I firmly believe that ROI is not determined solely by a student’s major. Students make hundreds of choices in college—some small, some transformational—that shape their outcomes. Their ability to navigate the hidden curriculum (the unwritten rules of higher ed), take advantage of co-curricular and experiential opportunities, and develop professional networks can significantly impact their career trajectory and earning potential. Two students with the same major from the same school can have wildly different outcomes based on how they filled in the “blank spaces” of their college experience.

This idea is central to the concept of a “field of study,” as discussed in Hacking College by Laff and Carlson. They argue that students should approach college not as a checklist of requirements, but as an opportunity to construct a personal academic and career narrative by integrating general education, major courses, electives, and hands-on experiences around a central vocational purpose. Field of study reframes the college journey as one of exploration, synthesis, and strategy—especially important for students who may not enter college with the cultural capital to see all the options available to them (Laff & Carlson, 2025).

In that framing, ROI becomes less about simply picking the “right” major and more about cultivating agility and intentionality. As the authors note, students who actively shape their undergraduate experience around real-world problems and interdisciplinary curiosity are more likely to find meaningful work—even if their major wasn’t associated with the highest median salary on graduation day.

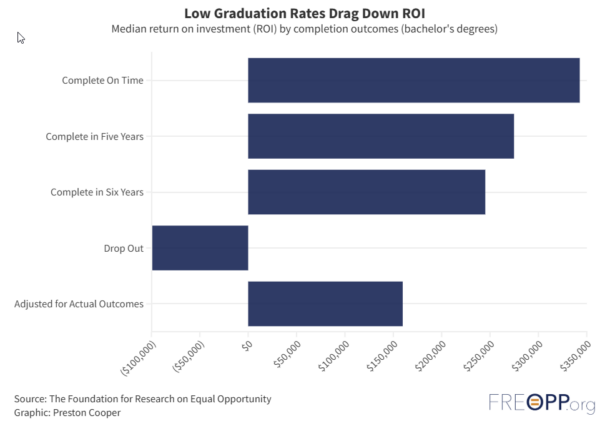

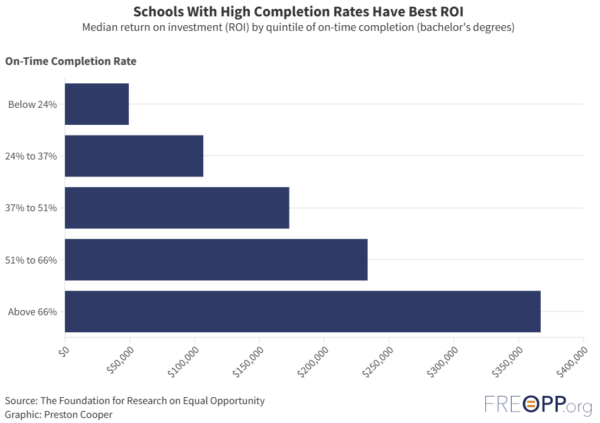

Importantly, both the CEW and FREOPP studies attempt to bake in the real-world risks that students face—especially the risk of dropping out. As the FREOPP report notes, ROI is highly sensitive to whether students finish their programs. The graph below shows how programs with low graduation rates tend to deliver significantly lower returns—even when the major is in a high-demand field. Completion isn’t just a personal milestone; it’s a financial hinge point.

FREOPP’s model adjusts for the fact that a degree doesn’t pay off if you don’t finish it, and CEW includes the earnings of both completers and non-completers in their estimates, making their numbers more representative of actual student outcomes (Cooper, 2024; Cheah et al., 2025). This is especially relevant for adult learners and first-generation college students, who often face steeper barriers to completion and carry greater financial risk.

In short, both the FREOPP report and the CEW study help clarify a complicated picture. While their numbers don’t always align perfectly, they converge around several key insights:

- College is still a good investment on average.

- ROI varies dramatically by program and institution.

- The timeline to see a return can be decades, not years.

- Student choices and institutional structures both shape the final outcome.

- And for many students, especially those balancing work, family, and finances, the journey to positive ROI is a long one—but not a passive one.

As we’ll explore next, that long timeline is one of the biggest barriers to how students perceive value. Even when a degree pays off in the long run, the financial pressure in the short term can make it hard to feel like a smart investment.

The Time Trap: Why ROI is Hard to Feel

Even when the math shows that college pays off, it often doesn’t feel that way—especially in the early years after graduation. That’s the challenge at the heart of college ROI: the payoff is real, but for many students, it’s also distant, delayed, and emotionally disconnected from the financial pressures they face right now.

Both the FREOPP report (Cooper, 2024) and the CEW study (Cheah, Van Der Werf, Morris, & Strohl, 2025) confirm that college degrees tend to yield strong lifetime returns. According to CEW, the median ROI for private nonprofit institutions in North Carolina at the 40-year mark exceeds $800,000—and it’s even higher for selective institutions. FREOPP finds that nearly 75% of bachelor’s programs nationwide deliver a positive return, with many health, engineering, and business degrees yielding returns over $500,000.

But here’s the problem: those are long-term gains. CEW’s model shows that for many programs, it takes 10 to 15 years just to break even—especially when factoring in net price and lost wages during college. Some degrees take even longer. At over 1,200 institutions in CEW’s dataset, the net financial return to students is negative at the 10-year mark. That’s a long time to wait when student loan payments kick in just six months after graduation.

The FREOPP report tells a similar story. While the majority of bachelor’s programs eventually produce a positive ROI, the timing of that return varies widely. In North Carolina’s private nonprofit colleges, we see strong long-term ROI for programs in nursing, business, and computer science—but far more modest or even negative returns in fields like fine arts, theology, and some education programs, particularly at the master’s level. That’s not a judgment on the value of those fields—it’s a reflection of current labor market realities.

And yet, many students from these programs enter careers with purpose and meaning—just not high salaries. The real difficulty is that the cost of attending college is immediate and steep, while the benefits are distributed slowly over decades. Monthly loan payments, housing costs, and entry-level wages don’t leave much room for the long view. For recent graduates, especially those supporting families or living paycheck to paycheck, the phrase “college pays off in the long run” can feel almost cruel.

This is especially true for students from low-income backgrounds or first-generation college-goers, who are less likely to have financial safety nets and more likely to work during school—stretching time-to-degree and increasing the odds of leaving without a credential. Even when they do graduate, they often lack the networks or internship experiences that help turn a degree into a job quickly (Cooper, 2024; Cheah et al., 2025).

Hacking College digs into this issue through its discussion of “blank spaces” and the hidden curriculum. Many students are handed a roadmap to degree completion—but not a real strategy for turning that degree into a launchpad. They’re told the major will lead to a job, but they aren’t coached on how to explore the hidden job market, identify mentors, or build social capital along the way (Laff & Carlson, 2025). In the absence of that support, too many students check the boxes but leave college unsure how to connect their studies to a career. The financial anxiety that follows can erode even the most promising ROI.

And here’s where we have to be honest: time isn’t the only hurdle. Emotionally, psychologically, and practically, the delayed nature of ROI asks students to act on faith—to make a large, often debt-financed investment in something that won’t pay off for a decade or more. That’s a big ask, especially in a world where alternatives like short-term credentials or skilled trades can offer faster, more visible returns.

In fact, CEW’s report notes that certificates and associate degrees often yield higher ROI than bachelor’s degrees for the first 10 to 20 years after enrollment. For students with immediate financial needs, those faster-paying credentials may be the smarter choice. But over time, the gap widens. By year 30 and 40, bachelor’s and graduate degrees typically overtake short-term paths—not just in cumulative earnings but in access to professional advancement and long-term economic mobility (Cheah et al., 2025).

Still, the timing challenge is real. As one Hacking College student story illustrates, even a student who “did everything right”—picked a major, followed the degree audit, and graduated—can leave college with debt, anxiety, and a sense of lost potential if they didn’t have the right conversations or connections along the way (Laff & Carlson, 2025).

Ultimately, the time trap is about expectations. We’ve sold college as a guaranteed ticket to prosperity, but the timeline and path are far more complex. Some also point to the inherent, intangible value of being a well-rounded and well-educated individual—a contributor to society, a critical thinker, a lifelong learner. And those benefits are real. But they aren’t sufficient justification for going tens of thousands of dollars into debt without a clear and timely pathway to financial stability.

That’s why students need better tools, clearer guidance, and more transparent data—not just on what college costs, but how long the payoff takes and how to maximize it through every decision they make along the way.

What the Data Shows: Highlights from NC and SC

At the national level, the data on college ROI tell a consistent story: college is still a good investment for most people over time, but the scale and speed of that return vary dramatically by program, degree level, and institution. The same patterns hold true in North Carolina and South Carolina—and when you drill down into specific programs, the contrast between high-ROI and low-ROI degrees becomes even sharper.

Let’s start with some broad context. According to the Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce (CEW), over 60% of private nonprofit institutions in the U.S. deliver a positive ROI by year 10—and by year 40, that number jumps to nearly 95% (Cheah, Van Der Werf, Morris, & Strohl, 2025). The median 40-year ROI for these institutions is $918,000 nationally. In North Carolina, private nonprofits like Duke, Davidson, and Wake Forest perform exceptionally well in CEW’s model, but so do lesser-known schools like Gardner-Webb and Meredith—especially when measuring ROI at 30 and 40 years.

The FREOPP report, authored by Preston Cooper (2024), offers even more granular insight by calculating ROI at the program level. This means we can see not just how an institution performs overall, but how specific degrees—say, a B.A. in Psychology versus a B.S. in Nursing—stack up against each other. Using the data compiled from North Carolina’s private nonprofit schools, several clear trends emerge:

Undergraduate ROI Trends in North Carolina:

- High-ROI fields include nursing, computer science, finance, and business administration. These programs often show lifetime ROI well above $500,000, even at smaller or regional institutions.

- Low-ROI or negative-ROI fields include theology, music performance, and some visual and performing arts programs. In a few cases, bachelor’s programs in these fields had negative ROI estimates—meaning students may earn less over a lifetime than peers who entered the workforce directly out of high school (Cooper, 2024).

- Even within the same institution, ROI can vary widely. One NC college, for example, has a business program with a lifetime ROI of over $600,000—while its education and English programs are estimated below $50,000.

This variability reinforces a core theme from earlier: the major matters as much as the institution, if not more.

Graduate ROI: A Riskier Bet

The picture gets murkier at the graduate level. Nationally, the FREOPP report shows that more than 40% of master’s programs have negative ROI, especially in the arts, social work, and education fields (Cooper, 2024). In North Carolina, some master’s in education programs show positive but modest ROI—often under $100,000 over a lifetime. In contrast, graduate degrees in health sciences or business tend to deliver much stronger returns.

This aligns with findings from EducationData.org, which note that ROI at the graduate level is less predictable and highly dependent on program cost, market demand, and opportunity cost. Many graduate students are older, have families, or are balancing full-time work—so the timeline for payoff becomes even more complex (EducationData.org, 2023).

South Carolina Snapshot

Trends in South Carolina’s private nonprofits look similar to North Carolina’s. Nursing and business remain strong at the undergraduate level, with several programs showing ROI above $500,000. Meanwhile, fields like fine arts, religion, and interdisciplinary humanities lag behind. Graduate-level ROI is mixed, and again, master’s programs in education often show returns that are positive but small—and, in some cases, negative.

Download the Data

To help make this information more accessible, I’ve compiled two downloadable spreadsheets for readers to explore (see below):

- One with combined ROI data for North and South Carolina private nonprofit institutions from the CEW study

- One with program-level ROI data from FREOPP, including both undergraduate and graduate programs

These datasets can help students, families, and institutions dig deeper into ROI trends by program, school, and region—and use that information to make smarter, better-informed decisions about the true value of a college degree.

Beyond the Numbers

It’s important to stress: low financial ROI doesn’t mean low value. The TIME article Can Young People Afford to Not Go to College? makes this point well. While annual salaries may be modest, college still provides non-monetary benefits—like personal growth, critical thinking, and social mobility—especially for students from historically underserved backgrounds (Olian, 2025). But we also have to acknowledge that those intangible benefits don’t always translate into financial stability—particularly when students are saddled with debt and entering low-wage sectors.

That’s why the Forbes article on college ROI urges institutions and policymakers to go beyond “college = good” messaging. Instead, they argue for transparency and reform—helping students identify high-ROI pathways and holding institutions accountable for chronically underperforming programs (Dorfman, 2024). Students deserve to know not only whether college will pay off, but how long it takes and what they can do to increase the odds.

FREOPP Report – Data for ROI by program (undergraduate and graduate) offered by private not-for-profit in North Carolina.

CEW Report – Data for ROI by institution (undergraduate) for private not-for-profit schools in South and North Carolina.

Reframing the Conversation

For years, conversations about college value have bounced between two extremes: on one side, the belief that a college degree is an automatic path to success; on the other, the claim that it’s an overpriced scam that leaves students with debt and no direction. The truth, as is so often the case, lies somewhere in the middle. But to really support students—both those entering college and those thinking about returning—we need to change how we talk about return on investment.

First, we need to stop treating ROI like a fixed number on a spreadsheet. While the data from the FREOPP report and the CEW study provide invaluable benchmarks, they don’t capture the full story. A degree’s ROI isn’t just about what you major in or how much money you make right after graduation. It’s also about how well students understand and navigate their college experience—how they choose electives, pursue internships, engage with mentors, and align their education with a personal sense of purpose.

That’s why I appreciate the framework laid out in Hacking College by Laff and Carlson. They argue that we need to move away from a narrow focus on majors and start teaching students to think in terms of a field of study—a holistic, flexible approach to crafting an undergraduate experience around a real-world problem or vocational purpose. This approach encourages students to use every part of the degree—the general education courses, electives, projects, and co-curriculars—to build a more integrated and useful foundation for life after college (Laff & Carlson, 2025).

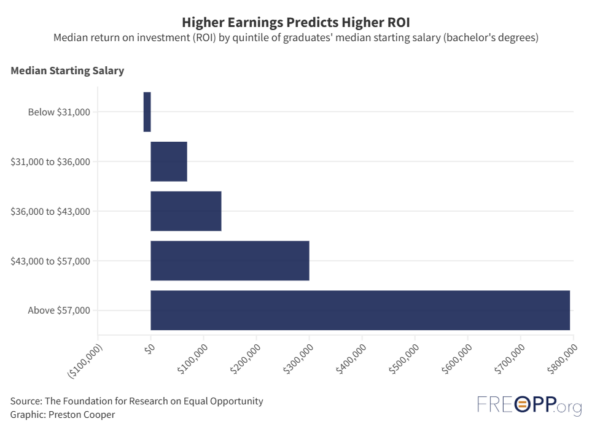

In short, ROI isn’t something students just receive—it’s something they can help shape. But only if they’re taught how. As the FREOPP data show, ROI is strongly tied to earning potential—but that potential isn’t determined by major alone. The graph below illustrates that higher post-graduation earnings are the strongest predictor of ROI, but it also reinforces the importance of student choices: internships, skill development, and experiential learning can all help graduates raise their earning potential and realize stronger returns.

That’s where institutions have a huge role to play. Too often, students—especially first-generation or adult learners—are ushered through the system via transactional advising and rigid degree audits. They’re told what boxes to check but not how to connect their education to their goals. As Hacking College makes clear, even highly motivated students can end up with what the authors call an “empty college degree”—a collection of credits that meets graduation requirements but lacks any meaningful connection to a job, graduate program, or deeper purpose.

We also need to rethink our academic structures through the lens of equity and efficiency. One of the most effective—but underutilized—strategies is expanding Competency-Based Education (CBE) and Credit for Prior Learning (CPL). These tools give credit where it’s due—recognizing learning that has occurred outside the classroom through work, military service, volunteerism, or other lived experience. And they have powerful effects: CAEL’s research shows that receiving CPL boosts adult learner completion rates by 17%, while also saving students significant time and money (Council for Adult and Experiential Learning [CAEL], 2022; Swabek & Fowler, 2025).

Consider the example of the University of Maryland Global Campus (UMGC). Students who transferred in ACE-recommended Sophia Learning courses had a 47% higher continuation rate to their second term and were 86% more likely to be enrolled by their fourth term than their peers (CAEL, 2023). Similarly, College Unbound redesigned its CPL program with student voices at the center, tripling the number of students earning CPL in just three years. By the time of graduation, 96% of their students had earned CPL, accelerating time to degree and reducing costs—especially for students of color and those with caregiving responsibilities (Cleary, 2023).

Yet despite the benefits, uptake remains far too low. Nationally, only 11% of adult learners earn CPL, even though 80% of institutions offer it (CAEL, 2020). The equity paradox here is stark: Black, Hispanic, and low-income students are the most likely to benefit from CPL—but the least likely to receive it. The reasons are systemic—ranging from lack of outreach to institutional bias about what counts as “creditworthy” learning.

Even when CPL is earned, it’s not always honored across institutions. Many colleges still won’t accept CPL in transfer, frustrating students who’ve already demonstrated their learning. CAEL and AACRAO have called for standardized, high-quality practices for evaluating and transcripting CPL, noting that poor transferability is a major obstacle to realizing its full impact (Flaherty, 2024; Swabek & Fowler, 2025).

Fortunately, best practices are emerging. The UNC System recently launched a Military Equivalency System to match service experience with credit at 16 public institutions. Purdue University Global and Ivy Tech created a model to prevent duplicate CPL awards by embedding clear CPL indicators in student records. And schools like Front Range Community College are showing students exactly how much time and money they can save through CPL—on average, $1,600 to $6,000 (Flaherty, 2024).

These aren’t fringe experiments—they’re practical, equity-driven strategies that improve student ROI. But they require intentional investment, cross-institutional collaboration, and cultural change.

As CAEL has long argued, recognizing learning in all its forms is not a shortcut—it’s a pathway to equity, affordability, and adult student success. If we’re serious about increasing ROI for today’s learners, then CBE and CPL must be central to that strategy—not optional extras (CAEL, 2022; CAEL, 2023; Cleary, 2023).

And we must continue removing barriers—academic, financial, or bureaucratic—that slow students down or block recognition of what they’ve already achieved. As Melanie Booth from the Higher Learning Commission puts it, “CPL isn’t just a tool for degree acceleration—it’s a bridge between learning, work, and upward mobility” (Flaherty, 2024).

The bottom line is this: college ROI is real, but it’s not guaranteed. And it’s certainly not automatic. It depends on the structure of the institution, the intentionality of the student, and the alignment between educational experiences and career goals. If we want to keep higher education relevant—and restore public trust in its value—we need to move from oversimplified promises to empowered planning and informed decision-making.

The ROI is Real, But so is the wait

As we’ve seen throughout this exploration, the return on investment for a college degree is not a myth. It’s backed by data, shaped by experience, and confirmed by countless individual stories. But that doesn’t mean it’s immediate—or easy to access.

The reality is that college ROI is real, but so is the wait.

For many students, especially those taking on debt or juggling school with work and family, the payoff can feel abstract and painfully delayed. When it takes 10, 15, even 20 years to truly realize the financial benefit of a degree, it’s no wonder that skepticism has grown—especially in a world where rising costs and stagnant wages make each financial decision feel more consequential.

But this isn’t just about money. It’s about trust. When we tell students that education is the key to a better life, we need to back that up with clear, honest, and actionable pathways. That includes transparency around earnings data, cost, time-to-degree, and career outcomes. It also means redesigning the system to make that ROI easier to reach—through better advising, expanded CPL and CBE, more flexible formats, and degrees that adapt to shifting workforce needs.

And we have to stop talking as though the only “real” college student is 18 years old and living on campus full time. Today’s learners are as likely to be 35 as they are to be 19. Many are returning to college to finish a degree, switch careers, or earn a credential that unlocks a promotion or new opportunity. These students deserve pathways that respect their time, honor their experience, and accelerate their journey forward.

To do that, institutions must move from gatekeeping to goal-setting—from sorting students by what they lack to supporting them in building on what they’ve already done. One of the most consistent ROI predictors isn’t selectivity or endowment—it’s whether students graduate. As shown in the graph below, institutions with higher completion rates tend to deliver much stronger ROI. For colleges and universities, this underscores the moral and financial imperative to support persistence and completion for all students.

And students, in turn, must be empowered not just to choose a major, but to shape a meaningful field of study that reflects both who they are and where they want to go.

At its best, college doesn’t just train workers. It equips people to adapt, reflect, collaborate, and lead. But for that to be sustainable—for individuals, families, and society—we need to reckon with the cost and pace of that payoff.

I don’t claim to have all the answers. But if I’ve learned anything from two decades in higher education, it’s this: students will rise to the occasion when given the tools, information, and respect they deserve. Our job is to build systems that earn their trust—and make good on the promise we’ve made for generations: that education can lead to a better future.

Yes, the ROI is real. But we still have work to do to ensure that everyone—not just those with wealth, privilege, or inside knowledge—gets the chance to realize it.

Final Thoughts

If we’re serious about strengthening the return on investment of a college degree, then we have to shift more of the responsibility to the institutions themselves—not just the students navigating them.

Colleges and universities can no longer rely on tradition or reputation alone. They must be proactive in reducing costs for students through strategies like expanding Credit for Prior Learning (CPL), creating clear and generous transfer pathways, and shortening time-to-degree wherever possible. These aren’t just administrative fixes—they’re equity strategies that directly affect whether a student can afford to persist and finish.

But lowering costs is only half the equation. Institutions also need to focus on raising the value of what students experience once they’re enrolled. That means helping them understand and navigate the hidden curriculum—the norms, networks, and unwritten rules that often determine who gets access to high-impact opportunities like internships, mentorship, and leadership roles. It means making the most of co-curricular and extracurricular learning, where students develop the professional and interpersonal skills that employers consistently value. And it means embracing a more holistic field of study approach, where students actively construct a pathway that reflects their goals, their strengths, and the real-world challenges they want to solve.

Increasing ROI—and accelerating how quickly students realize it—requires this kind of institutional intentionality. We cannot continue placing the entire burden on students to figure it out on their own.

Whether someone is 18 or 38, working full-time or coming straight from high school, they deserve a college experience that is transparent, empowering, and worth the investment. The data makes one thing clear: college can absolutely pay off. But it’s on all of us—faculty, staff, administrators, and policy leaders—to ensure it pays off more consistently, more quickly, and more equitably for everyone who walks through our doors.

References

California Competes. (2020). Credit for prior learning and competency-based education: Tools to boost adult learning and close equity gaps. https://californiacompetes.org

Carlson, S., & Laff, N. (2025). Hacking college: Navigating the broken promises and evolving needs of higher education. Johns Hopkins University Press.

Cheah, B., Van Der Werf, M., Morris, C., & Strohl, J. (2025). The college payoff: More education doesn’t always mean more earnings (2025 update). Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce. https://cew.georgetown.edu/cew-reports/college-roi-2025/

Cleary, K. (2023, September 27). Increasing equity with credit for prior learning [Opinion]. Inside Higher Ed. https://www.insidehighered.com/opinion/views/2023/09/27/increasing-equity-credit-prior-learning-opinion

Cooper, P. (2024). Does college pay off? A comprehensive return on investment analysis. Foundation for Research on Equal Opportunity. https://freopp.org/does-college-pay-off-50b2fbd8d3c7

Council for Adult and Experiential Learning. (2022). Partners in a new learning model: Credit for prior learning and competency-based education. https://www.cael.org

Council for Adult and Experiential Learning. (2023, June 22). Research shows retention gains through credit for prior learning. https://www.cael.org/resources/pathways-blog/research-shows-retention-gains-through-credit-for-prior-learning

Council for Adult and Experiential Learning. (2025). State of undergraduate credit for prior learning report. https://www.cael.org

Flaherty, C. (2024, January 5). Push for colleges to accept more credit for prior learning. Inside Higher Ed. https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2024/01/05/push-colleges-accept-more-credit-prior-learning

Olian, J. D. (2025, March 13). Can young people afford to not go to college? TIME. https://time.com

Swabek, T., & Fowler, D. (2025). Credit for prior learning mobility: Possibilities and practice from the field. Council for Adult and Experiential Learning. https://www.cael.org